David's Spiritual World

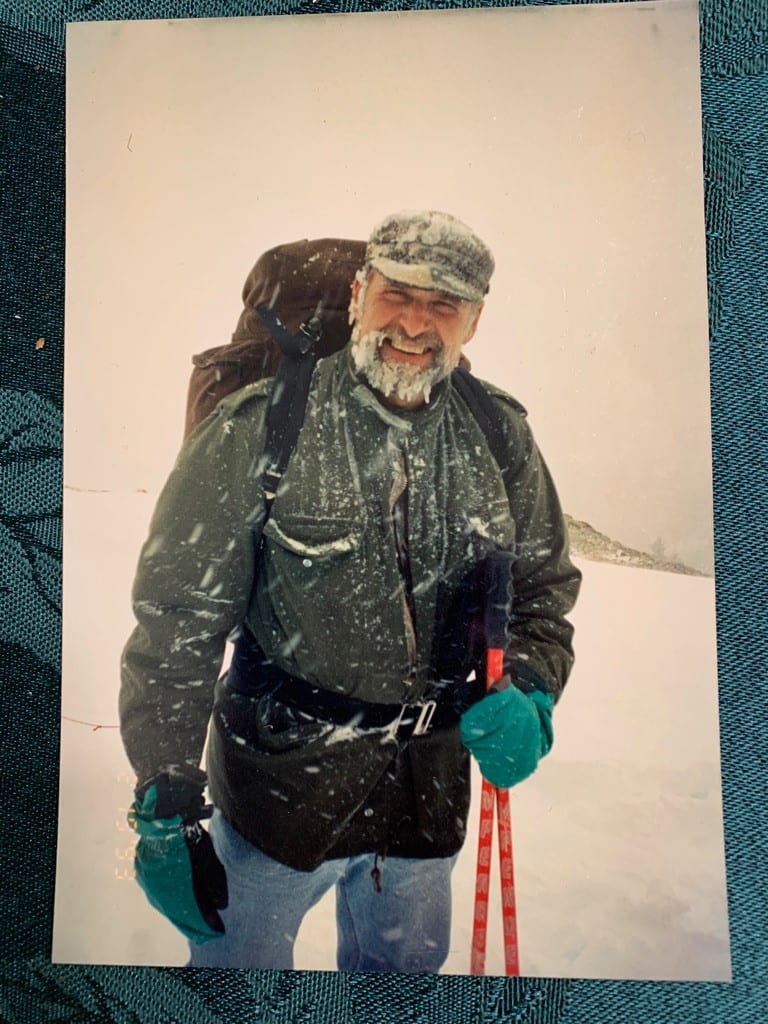

David Moss has spent the entirety of his life in the service of others. He is one who lives what he believes. David is a member of the Miller-Leeper clan to which Dunrovin Ranch owners Sterling and SuzAnne Miller also belong. David is married Sterling's stepsister, Cedar.

Born in 1943, David graduated in 1969 as a Master of Sacred Theology from Boston University and was a research fellow in the Yale Divinity School. He served as an ordained elder in the United Methodist Church from1969 through 2009. Serving seven different churches in norther California, he spent years working with the homeless and the mentally ill Sacramento, California through an organization called Loaves and Fishes. Upon retiring from the organization, David wrote about The 36 Things he had learned from his time being with their guests. As a board member of the Global Mission for the United Methodist Church, David traveled several times to Palestine and Israel as part of Christian Peacemaker Teams.

David is as gentle and kind a person as you will find. A born storyteller, David loves to write about the many people he has encountered along the way. His years of service, study, and prayer have given him a unique perspective on the world which he beautifully conveys in his stories, which are full of understanding, compassion, and grace.

Avalanche

Story 1

By Davie Moss

I ride through Lassen National Park on my motorcycle. It is August 25, 2017, but up here on the top of the Sierra Nevada range it is only spring. Grass is still green from the melting snows. Tiny flowers of mountain mint have the potent fragrance of decanted essences in this purified air above 8000 feet. I pick a handful and stuff it in my pocket.

I ride through Lassen National Park on my motorcycle. It is August 25, 2017, but up here on the top of the Sierra Nevada range it is only spring. Grass is still green from the melting snows. Tiny flowers of mountain mint have the potent fragrance of decanted essences in this purified air above 8000 feet. I pick a handful and stuff it in my pocket.

I’ve parked my bike at a lookout on the edge of a vertical precipice 200 feet deep. There are no guard rails here or on this narrow two lane black top. Route 89 winds closely around a huge boulder ahead of me.

It is here at this point that, on January 31, 2001, my friend Denis Eucalyptus and I found an intimate relationship with death.

We had been snow camping a mile further up that day in January when at 2am I woke to the sound of snow striking the tent, sounding like a hundred little mice scratching the fabric. A thick yellow front was gliding before the full moon, dark with menace. It arrived six hours early.

By morning light the wind was fierce, whipped the tent nylon like an old green flag. Nearby trees swayed, ghostly pale in the driving snow. We decamped immediately.

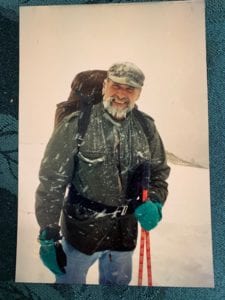

Packs on, ski’s clipped, we began the long trip to the trailhead at about 10am. The tracks we’d made the day before had already disappeared, smothered in a foot of new powder. We found unplowed Route 89 and started down, the snow flying at our faces.

Through the howl of the wind I heard the muffled roar of an avalanche across the canyon. I asked Denis if we shouldn’t dig a snow cave and wait out the storm. Denis is not one to be frightened by a storm. He said, Let’s go on. The trailhead is all downhill from here. We can drive home before dark.

I remembered looking up through the thick flying snow to see we were about to traverse a steep slope with no protecting trees.

We decided to put on our avalanche cords, a pre digital device of brightly colored nylon designed to float on the surface of a cascading avalanche which would allow another person to follow it to the fallen friend, likely hidden below the depths. We learned later that to be effective an avalanche cord should be at least 100 feet long. Denis’ old cord was about 30 feet, broken and re-tied many times. Mine was newer, only 50 feet.

He had his on in no time. I couldn’t find mine. I asked him to open my top pack and pull out an extra cord. He did. I took off my gloves, tied the cord to one of my belt loops, all taking much longer in that wind and cold than you might expect. By the time I was done Denis had gone ahead, around the bend and out of sight.

I pulled my parka hood over my head, bent down to see his tracks, and followed.

Presently, as I sensed a faint brightness in the naked slope beyond the trees, I heard him shout, Time to advance! Assuming he was tired of breaking trail, I stepped up my pace to take my turn in front. Suddenly his tracks disappeared! I looked up to see a pile of blocks of snow in front of me, upwards of 20 feet high. It was then that I realized, with horror, that he’d said Avalanche!

This is where things begin to get blurry, time begins to flex, pressed into images, impressions; moments of clarity; the rest swept away. I was engulfed by the terror of this calamity as surely as my dearest friend.

My first cell phone - a primitive foldout with tiny black keys - not charged for three days. In the middle of wilderness surrounded by air thick with hundreds of miles of flying snow. Got through for three calls - just enough to get a rescue party going.

Denis had strapped our snow shovel on his pack. His avalanche cord had disappeared with his body.

I don’t see him down the canyon face. I hope to God he is on the road somewhere in front of me.

I assume from the sound of his last word, filtered through the roaring storm, that he is close. I plant my ski’s crosswise next to the front of the edge of the field, plant a pole on his fast disappearing tracks as reference, drop my pack, assault the wall of snow. I dig straight into the side of the mound. I use my hands and feet, kick at the snow, scoop it away, until the trench I start becomes a tunnel, becomes a cave, probing straight and horizontal, following the line of his tracks, poking in with one of my poles every few feet, hoping to touch his body; dig, scoop, probe, over and over again.

I really don’t know what else to do.

Overwhelming!

Denis’ life is in my hands, mine only. The seconds tick away. He is slowly suffocating to death just a few feet beneath my boots. But where! I work like one possessed because I am. I’m panting; sweating more than I expected, drinking the water bottle to a half cup that ends up freezing though I’ve placed it next to my shirt under my parka. I bust a manhole to the top, fearful of another falling catastrophe. I hear the wump of an avalanche, scramble out, look up, fearful I may be buried, entombed with my friend. This happens many times during the day as I continue to lengthen my cave: ten, twenty feet, etc…

When will they come?

Avalanche?

Rescuers?

Denis?

What will be first?

One overarching desire consumes me, to search until Denis is found; to drag him alive or dead to a place of safety around the curve of that road from which we’d come, away from this murderous field.

I cannot give up. I must not give up. I couldn’t live with myself if I gave up. I couldn’t face his wife if I gave up. To die is fearful. I cannot think of death. I give death up to fate or God. I must keep digging, never give up till I find Denis or until I’m released of the work or until I die. The sooner I find him the better his chances; the better both of us have; to live.

I yearn more than life itself that our rescuers come. Oh to see another human face up here, to be relieved of my duty, my responsibility. Oh to find Denis, to drink water, to rest, to feel warm again!

As the day goes on. Exhaustion overtakes me. I slow my pace.

After too many false alarms, sometime that afternoon I pop my head above my hole and see two men who’ve dropped their packs and are talking quietly nearby. They are Ski Patrol professionals. They’ve seen my crossed ski’s. Are you Denis? They ask.

No. Denis is under. I’m David…looking for him… I think he’s straight in front of me somewhere.

Frank and John give understated smiles, brief handshakes. Someone on the radio got your names mixed up. They return to their packs and pull out a sleeping pad, a space blanket and a large bottle of water. I must be shell shocked. I don’t act outwardly as desperate as I’ve been internally. Unspeakably grateful for their presence I start to relax. Hands and feet numb, my body doesn’t feel like my own anymore. It starts to shake. They put me back in the cave I’d made, away from the fierce winds. I sit on the pad, wrap myself in the blanket. I drink half the bottle of ice water in big gulps. I let them take over. I let go.

They begin their work to find Denis, begin with a brief tour of the cliff face below.

A Forest Service snow cat arrives full of rescuers. It parks one hundred yards away on the homeward side of the avalanche. I’m escorted, wobbly legs, to the warmth of the combat cabin, its engine running, its heater going full blast. Hydrated, I begin to feel my strength, to wake up.

It is getting dark. I hear the chatter over the static on the radio. They switch on their headlamps out there. I look at the turret hatch in the ceiling, see a large spotlight, grab it with both hands, open the hatch and beam the great light into the beyond. It follows the flying snowflakes up the mountain to the site where they were digging.

Soon thereafter Headquarters decides the danger is too great to sustain this operation. These men and women are exposed to another avalanche as they work. All day fresh snow has piled up above us. Statistics show that a person buried under an avalanche over 30 minutes will suffocate. This is clearly a recovery, not a rescue.

They begin to gather the gear, ready to head for home.

Frank and John do not stop. Frank sinks his 6 foot probe another time, one last few times before giving up, when he strikes a hand. This hand was the highest part of Denis’ body.

They start digging anew. Frank reaches into the hole upside down to touch Denis’ glove, pulls it out, reveals a hand inside. Then to his surprise, Frank hears a peculiar guttural sound: a kind of bubbly breathing! Denis is alive! Frank calls for oxygen!

They put him in a snow stretcher, tow him to the snow cat, place him in the cab with me. Everyone comes down.

I crouch over his ear. His whole body is in the same position He’d been when frozen in place 6 hours ago, cold as stone, his limbs rigid. Every muscle in his body is at war with its opposite in a complete body spasm; one huge Charlie horse!

I bend down to his left ear. Over the roar and vibration of the engine I whisper orienting thoughts all the way down. This is David, Denis. You are alive. We are going home together. You are going to be OK. You will see your dear wife soon. All’s well…

He does not respond, just keeps saying endlessly in a small little voice, Help me… Help me… Help me…

When we reach trailhead an ambulance is waiting. Emergency vehicle lights are flashing all over the darkened landscape. They take him away to the little hospital in Chester. I stay for a debriefing, thank each person who came so far away to help us.

I clear my jeep of snow. Everybody is leaving. The lights in the parking lot are turned off one by one. In deep shadow I reach in my pockets for the keys. I find the avalanche cord I thought I’d lost in the same pocket I’d searched so long ago…

It rushes through me, this naked sense of fear I’d kept damned up for 6 hours, washed through me like the avalanche, cracked inner walls like trees, ripped my psyche clean and raw.

At the hospital I enter Denis’ room. He looks at me and smiles! I kiss his cold damp forehead.

That morning he says he’d not panicked when the snow took him, packed itself hard around him. He’d barely had time to sweep the snow from his face before it set. He did not hyperventilate, avoided creating an impervious frozen shield around his face. It was hard to breathe with all the pressure packed in on him. He didn’t feel anything broken. Grateful, he said he’d imagined the mountain, Gia, loving him, giving him a big bear hug. So he took little breaths, thinking, “Thank You,” for each, one at a time, as it came, until he lost consciousness.

Later we heard that my wife Cedar and another woman in Denis’ parish, when they heard the news of the avalanche, prayed for us, breathed for us both in their prayers.

We do not know why we beat such overwhelming odds.

All that’s left is a deep gratitude for life: this sense of how blessed, like the Buddhists say, is each breath as it comes. And for me, I’ve got this new sense of what death is. It is this dark shadow behind me that I can almost touch if I reach back carefully with my left hand.

David Moss, September 13, 2017