Highland Lookout: My Launching Pad

by SuzAnne Miller

August 4, 2018

During weddings at Dunrovin Ranch, my husband Sterling and I escape by taking two-day trips to poke around Montana. Yesterday found me at the foot of the Highland Mountains where 52 summers ago I lived in a fire lookout as a US Forest Service employee. It gave me pause. I could not help but transport myself back to those summers. Never did I expect to see the 70-year-old version of myself looking up from a landscape that I had come to know like the back of my hand and that left an indelible imprint on my heart and mind.

The Forest Service had wisely asked me to create a "viewshed" map of all that was visible from the lookout. It took me days to draw out the lines and color in those portions of the mountains and valleys that I could see from those that were hidden. The process cemented in me a thorough knowledge of all that lay at my feet and instilled in me a lifelong understanding and love of maps.

As I gazed at the lonely perch on the mountain, I could feel the tug of the tether that binds me to that young woman. Some of the tether's filaments are frayed, some entirely broken, and some fade into ghost strings that evaporate into thin air. Others have solidified, petrified into granite-strong links that have supported me through time.

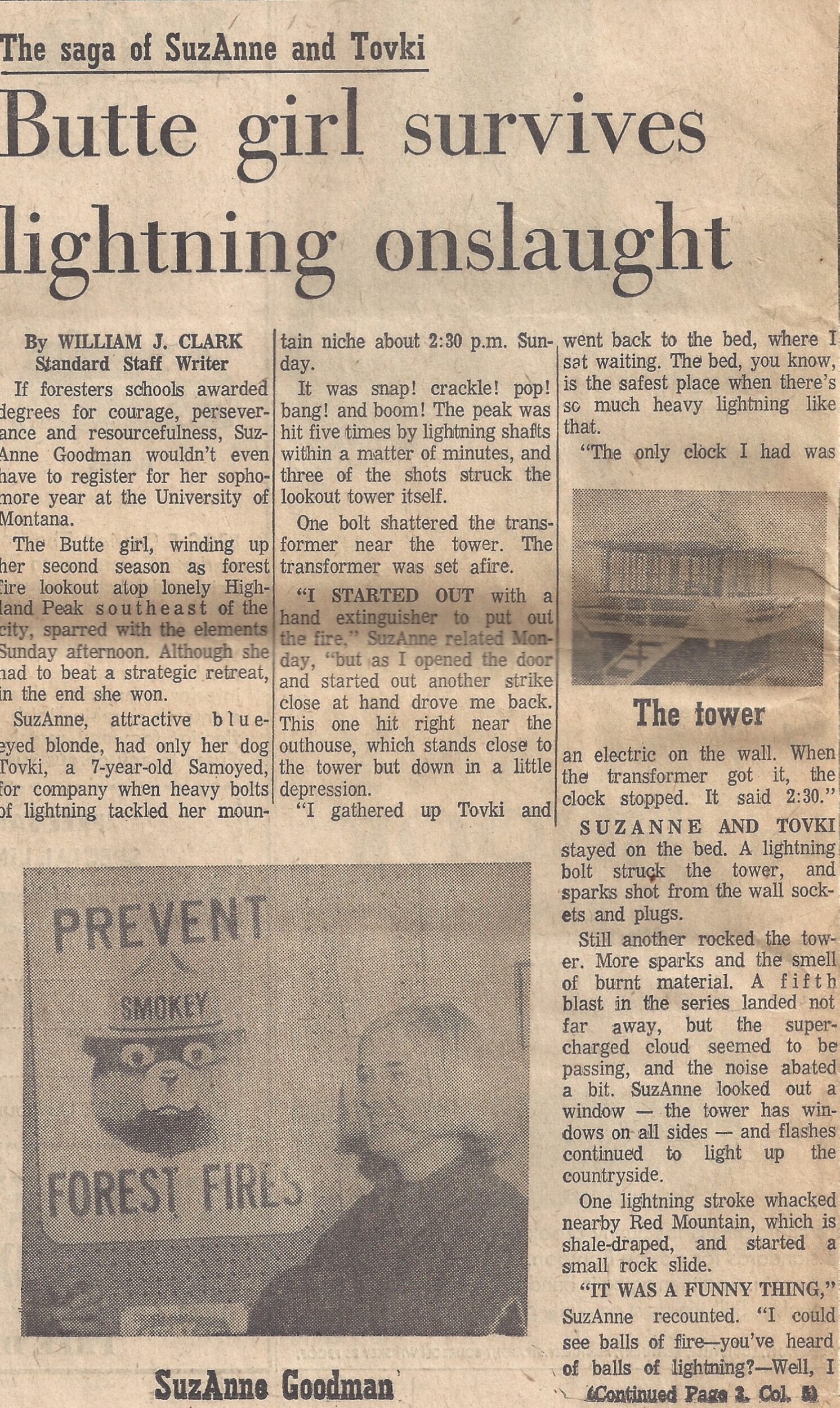

My days at Highland Lookout had been spent in reflection, anticipation, wonder, and yes, some fear. I was on the doorstep of becoming an adult. I had just graduated from high school and had yet to face any of life's challenges alone. Throughout the summer, my parents dutifully drove the nearly impassable road to the lookout to give me comfort, play endless rounds of three-handed pinochle after dark, and share home-cooked meals. The mountain was visible from their living room window, and every lightning storm found them watching with anxiety. Indeed, lightning struck the lookout often - but the ground wires held until the very last day of my second year when I was forced to abandon it after a strike had started a small fire. I put the fire out, hiked to the highway, hitchhiked into Butte, and reported it to the Forest Service. We went back up the next day to retrieve my things and close for the season. I never returned to live there.

This place is a seminal part of my history. It taught me to trust myself, be self-reliant, take risks, enjoy my own company in total isolation, and know and love a vast landscape that has scrolled across my mind during times of trouble. I am grateful to that young woman for having chosen this place as her launching pad—however much of her lives in me still.

More about Highland

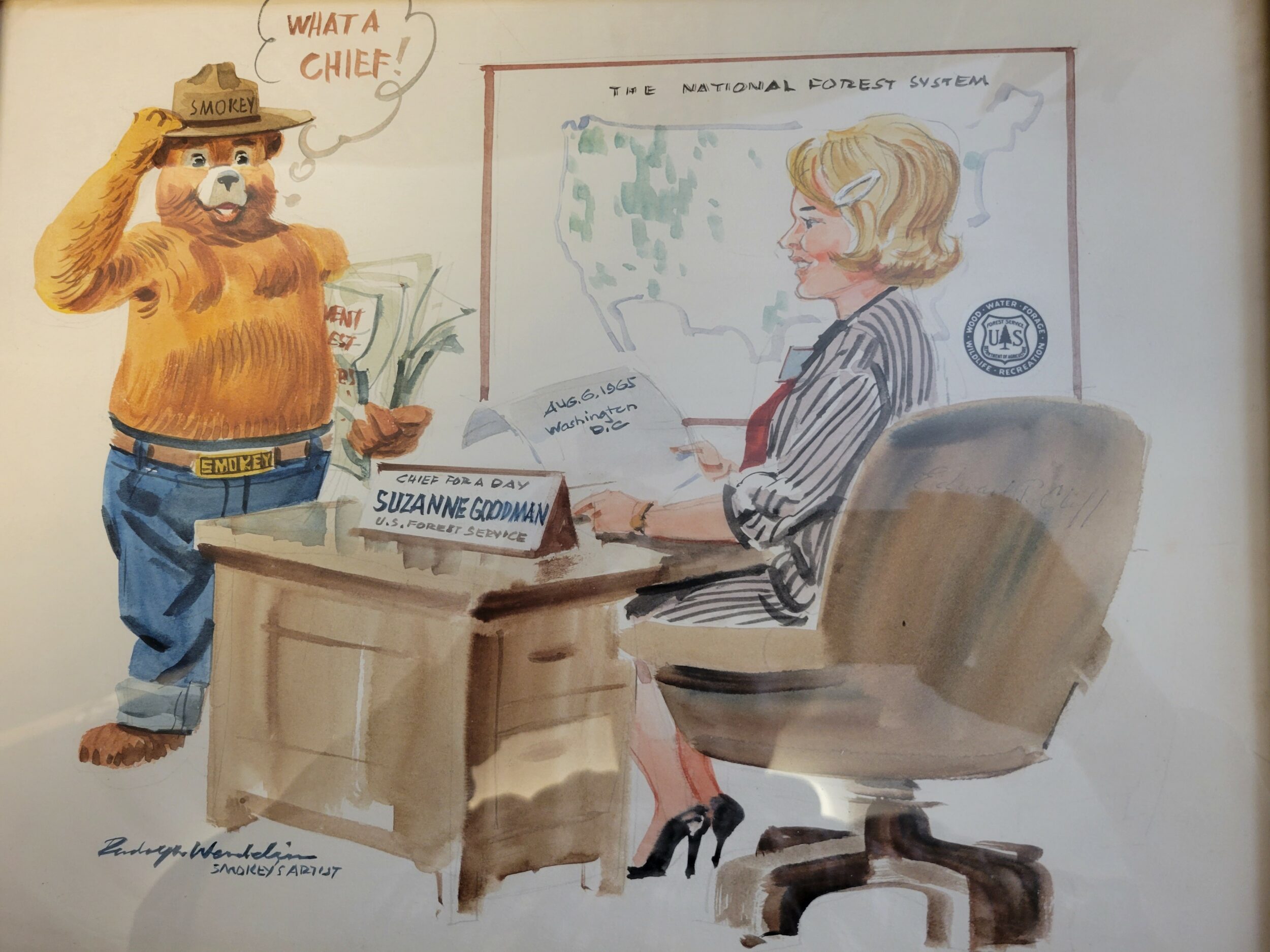

People often ask me how I came to get a job as a lookout with the Forest Service in 1966. While women have a long and proud history of manning fire lookouts, it was uncommon in the 1960's for a woman to be given a lookout job in Montana. I got the job through most unusual circumstances. In 1965 I was selected to attend Montana Girls' State which is a program sponsored by the American Legion Auxiliary to encourage young women to become knowledgeable and engaged citizens. While at Girl's State I was elected to represent Montana at Girl's Nation in Washington D.C. This precipitated my first-ever plane trip and allowed me to meet with the Chief of the Forest Service as that was the government post that I most wanted to interview as part of the Girls' Nation Program. I was the first Girls' National participant to ask to meet with the Chief of the Forest Service. They were surprised and delighted to host me and I ended up with a much longer and richer experience than most other participants. The Forest Service went out of its way to provide me with a meaningful visit - even getting their Smokey Bear artist to paint a picture of me as the Chief for a Day.

At the end of my visit, I was asked why I had chosen the Forest Service as the agency that I most wanted to interview. When I told them that I intended to study forestry and hoped someday to work for the agency, they offered to contact the local Montana National Forests to find me a summer job for the next year. The local personnel was not all that happy to have the national office basically dictate that I be hired, so they offered me a job on the highest and most isolated lookout in the region, assuming that I would either turn it down outright or only last a week before fleeing. I stayed for two seasons and loved every minute.

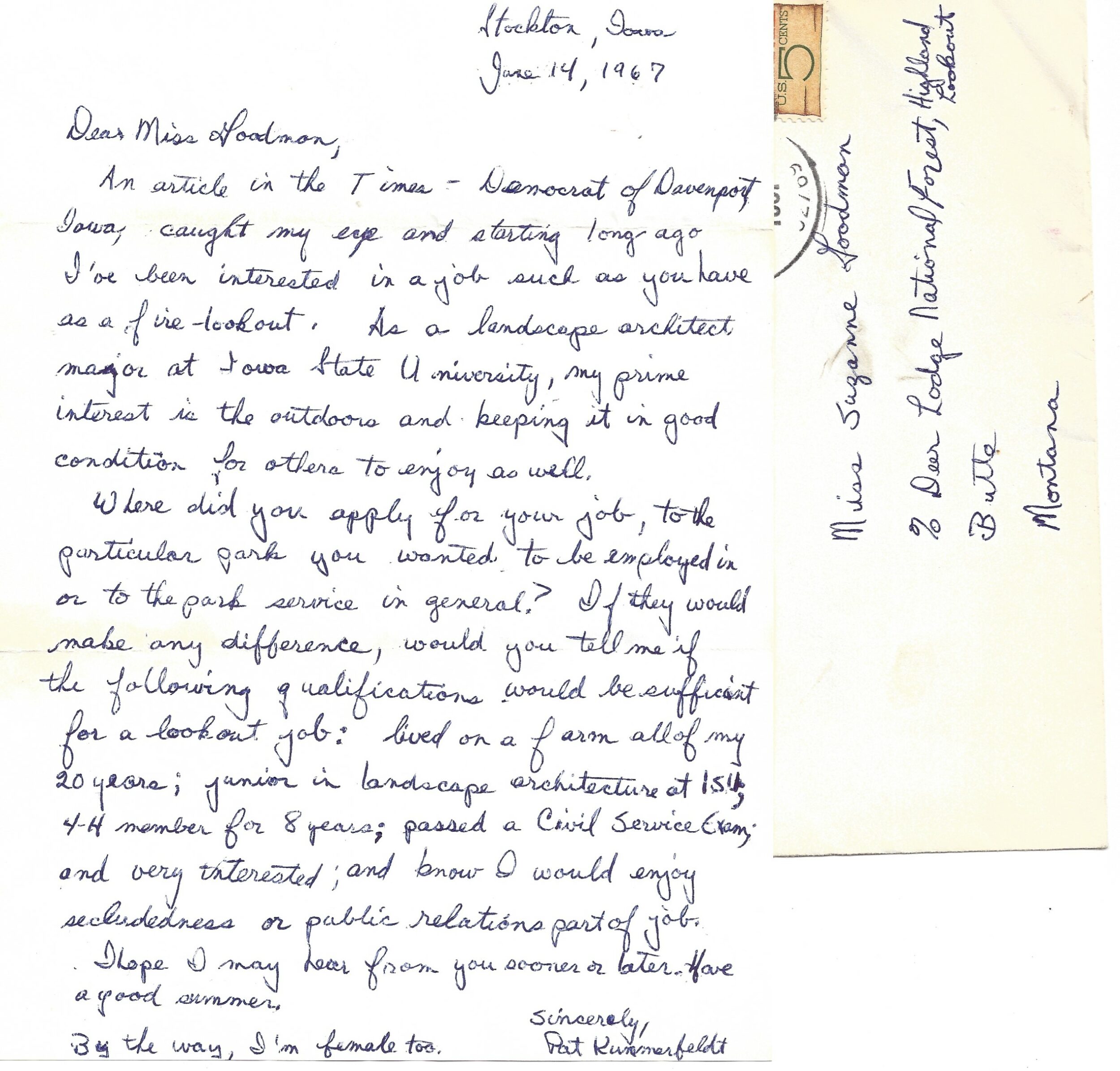

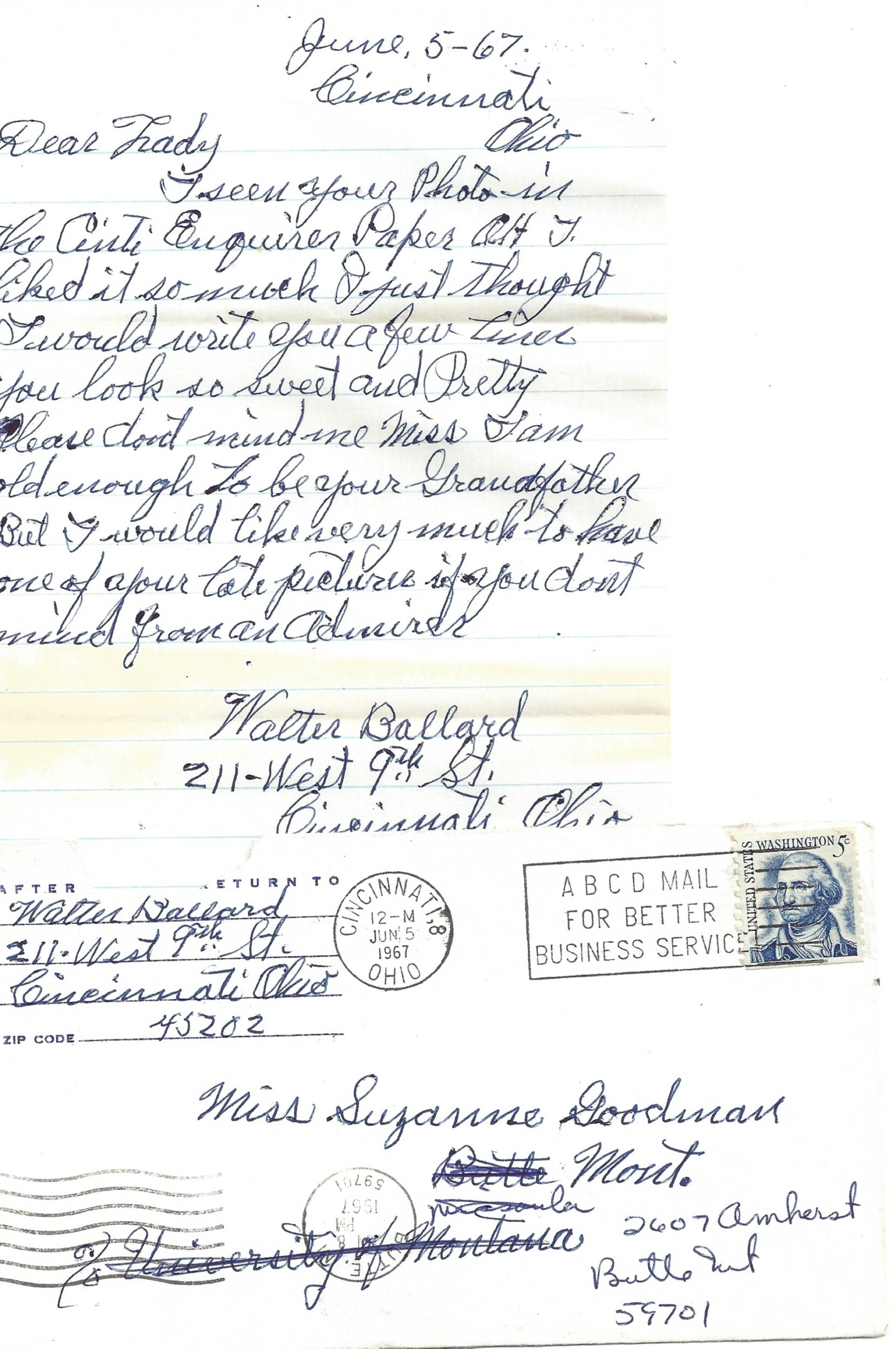

My presence on Highland was novel enough to generate a news article by the Associated Press International. My photo and a short description appeared in newspapers across the country and even in Europe. What I found interesting was that many people then wrote to me about the article. They did not have my address, but somehow the USPS was able to get a huge number of letters to me via the Forest Service who was, frankly, both amused and displeased. The letters covered a wide range of subjects: I received marriage proposals, a request to serve as the queen for a West Virginia wrestling club, scoldings from various religious groups saying that it was improper for a young lady to be living alone in the wilds, and letters from other women asking for information on how to get such a job

Lightning was a constant part of living at Highland Lookout. In fact, it was famous for it. The lookout tower I knew was actually the second one built there, The first one had been destroyed by lightning some years earlier. Part of my job was to count and map all the lightning strikes that occurred within a 20-mile radius of the lookout. My highest count for a single day was 1,329, and the lookout was struck 14 times. This data was part of a study called Project Skyfire.

Watching and mapping the lightning strikes enchanted me as I marveled at the power and drama of the skies. In the evenings, I often spoke via radio to other lookout towers, comparing storm notes. We soon learned to anticipate where storms were likely to move and predict which towers were in for a night of loud thunderclaps and blinding flashes of light. We also all understood that lightning strikes on the tower were less intense than those that struck close by when one is impacted by the full force of the released energy. Strikes to the tower were less dramatic as the energy moved away from the center (the tower) in all directions I also hosted a scientist at the lookout from the National Bureau of Standards who taught me a great deal about the physics of lightning and left a network of electronic equipment that I could monitor on the mountain in an unsuccessful effort to capture recordings of ball lightning that had previously been reported at Highland. I was fortunate to witness this unexplained phenomenon on two occasions during my summers there.

At the end of the second season, I was forced by lightning strikes to put out a fire, abandon the lookout, and head out on foot with my dog Tovki to return to Butte. This also made the news both locally and internationally which precipitated a second round of "fan" mail arriving from as far away as France and Panama.

With all that happened to me regarding Highland Lookout during that critical child-adult transition period in my life, it is easy to see why I view it as my launching pad that had a big impact on how my life unfolded. I carry its life lessons with me still.