Meet the Ospreys

Dunrovin wouldn’t be Dunrovin without our osprey nest and all the birds that visit us throughout the year. For years, ospreys have returned to Dunrovin to breed, build their nest, and rear chicks. It has been a fascinating and dramatic story that never ends. We named the first pair of ospreys Ozzie and Harriet. In 2014, we tragically lost Ozzie who was killed by an eagle. In 2015 we fretted about Harriet finding a mate as good as Ozzie had been. When one arrived, we shouted "Hallelujah" and named him Hal. But becoming Harriet's new mate was a long process. Every year, we anxiously await their return.

This video was produced in 2014 and talks about Ozzie and Harriet – but it also conveys our joy at having these wonderful birds in our backyard.

Dunrovin Ospreys Over Time

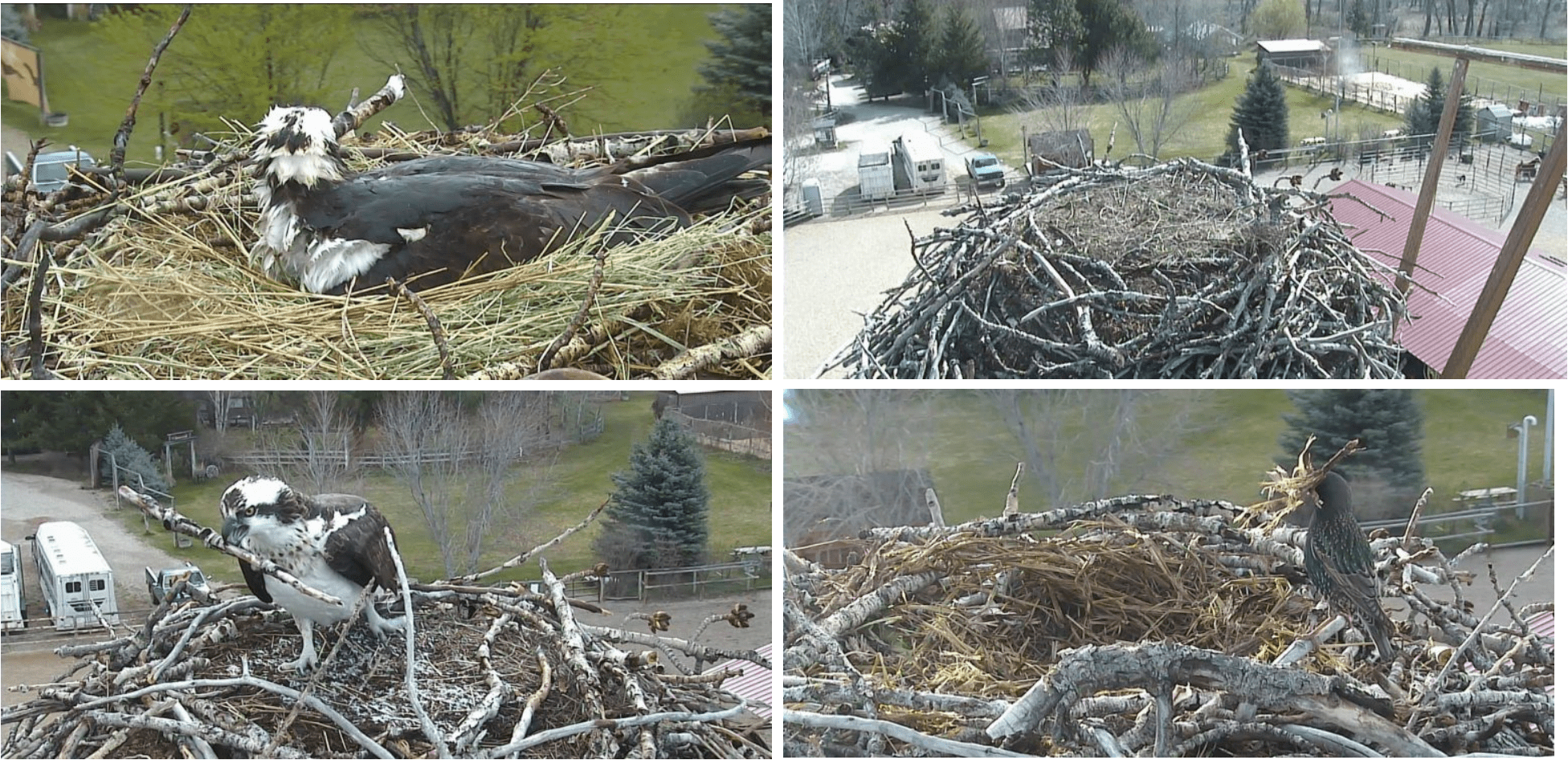

While the Dunrovin Ranch osprey nest has been here for over 30 years, the web camera wasn't installed until 2011. Since then, it sure has been a roller-coaster ride! Take a tour through time to get to know them and understand the enormous struggles they face to successfully raise chicks each year.

It's all about Harriet. Harriet Osprey has been the one constant throughout the years since we installed our web camera above her nest. She delights us. She amazes us. Her endurance, perseverance, dedication, strength, and total commitment to life have earned our respect, our admiration, and, yes, our love.

How is it that you can love an animal that you know only from afar, that you will never touch, and that knows you only as a two-legged being walking beneath her world and cares nothing about you? But I am not alone in my affections. Indeed, others who have never seen her personally, and probably never will, but who know her only through their computer screens via our web cameras love her every bit as much as I do. Mother osprey Harriet has fans all over the world. And she deserves them. Since 2011, we have watched this amazing bird lay a total of 15 eggs and successfully fledge 9 chicks.

Tour Through Time

It has been an amazing opportunity to watch Harriet these last six years. Each year has brought new challenges and she had met them all. Each year also brought changes to the nest structure and our web camera system, giving both us, and hopefully the ospreys, some additional enjoyment. Let's take a tour through time with Harriet starting when the web cameras was first installed.

2011

Dunrovin was approached by the University of Montana to allow them to set up a web camera above the osprey’s nest on an electrical pole near our barn. However, before installing the camera, everyone wanted to get the nest off of the electrical poles and asked the Northwest Energy Company for some help. Northwest Energy has a very active osprey program to try to keep them safe from electrical poles, which ospreys across the state utilize for nesting stands. Sometimes they use insulators on the poles with nests that prevent the birds from touching two wires and electrocuting themselves. In Dunrovin's case, they delivered and erected a new 47-foot pole nearer our barn and about 20 feet away from the electrical poles. They then moved the nest to the new pole, estimating that it weighted around 350 pounds.

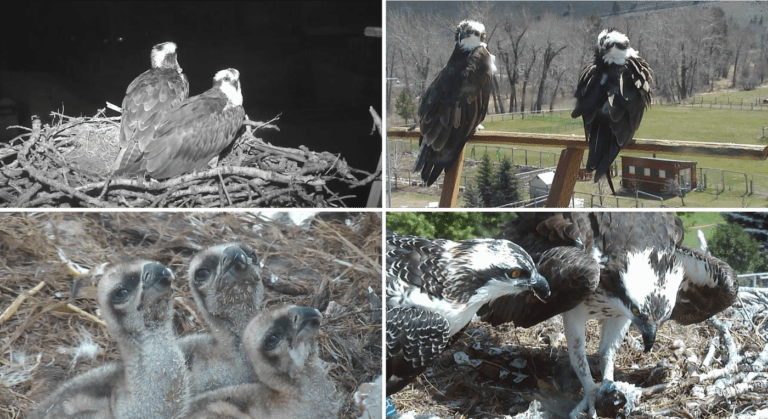

We really didn't know what to expect this first year. Dunrovin left all of the technical issues up to the university. We weren't even in a position to operate the camera. All we could do was view the camera from UM's website. It was very exciting for us to finally get to see the birds up close. Ospreys had been using the nest nearly every year since we moved here, and the nest itself was already huge when we purchased Dunrovin. But, before the web camera, we could never really tell if it was the same birds that returned each year.

We named the breeding pair that showed up, Harriet and Ozzie. They laid two eggs and fledged two chicks. We did not name the chicks. The UM scientists returned to band both chicks. Alas, one of the chicks was found dead along the Bitterroot River in late September, just before the adults and the surviving chick migrated south.

2012

Dunrovin replaced the university’s web camera with our own, high definition pan tilt zoom camera and installed an ambient microphone. We also took over the camera operations, partnered with Cornell University to broadcast our web camera their web site that featured a Twitter chat feature. Hundreds of thousands of viewers found us via Cornell and we began to engage with many of them via Twitter.

Everything was set for a season of viewing, but alas it turned out to be a very sad year for Ozzie and Harriet. They returned in late March and immediately set about nest building and mating. Their two eggs appeared in mid-April and everyone got very excited. Due to hatch near the end of May, thousands kept waiting to see a pipe, and we all kept waiting and waiting and waiting. Harriet and Ozzie’s eggs never did hatch. It was heartbreaking to watch the adults tenderly turn and sit the eggs, days, weeks after they should have hatched. They remained dedicated to those eggs for the better part of June, only reluctantly abandoning them. Harriet and Ozzie stayed in the area until early September, and then departed for their winter homes.

No one knew why. The University of Montana retrieved the one egg that was left in the nest at the end of the year to see if they could determine the cause. It was totally empty, indicating an infertile egg.

Sad to see Harriet and Ozzie depart as the summer season closed, everyone was already looking forward to the next year with high hopes for better success.

2013

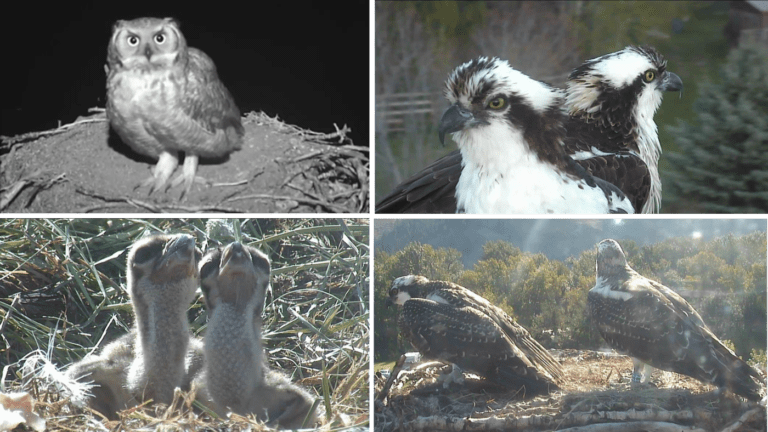

Thousand gathered around the nest on Cornell's web site that featured a Facebook plugin. We installed an infrared night light above the nest which neither humans nor birds can see but everything is visible through the camera. This gave all of us new perspective on the birds' activities.

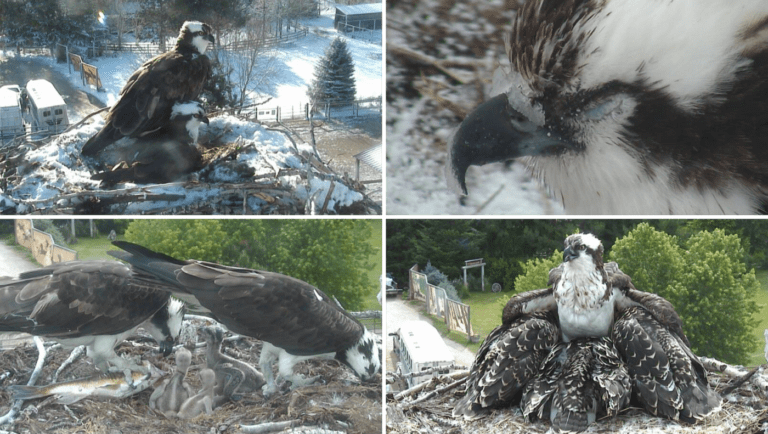

It was a joyous year, but also one of many trials. The first of Harriet and Ozzie three eggs was laid immediately before an unseasonably winter storm that froze Harriet's face and covered her with snow. Luckily, our inferred light enabled us to witness Ozzie relieving her of her duties during the night. When she got up to give him the egg, it was surrounded by warm and dry duff and perfectly safe. Two eggs followed, and this time all three eggs hatched. Hurrah! Dunrovin asked its many viewers to help it pick appropriate names for these darling little chicks. The most popular names proved to be Percy (for perseverance), Hope, and Dilly (for diligence).

There was little competition between the three chicks. Ozzie was able to deliver fish after fish to feed them all and they thrived. As if to punctuate the terrible winter storm that spring, the temperatures rose to over 100° under a relentless bright sun. For hours on end, Harriet spread her wings and stood silently with her back to the sun to provide shade for her growing chicks, who could barely fit all their three heads under her skirts. Nothing could stop Harriet from protecting her brood, not the ice of spring nor the oven of summer.

Again, the University of Montana scientists banded all three chicks, which later enabled us to keep track of at least one of them. Dilly was later seen on the Hellgate osprey nest web camera during the summer of 2015. Unfortunately, early in 2016, Dilly was killed by a car on the highway just north of Dunrovin. He had a fish in his talons. He was probably trying to gain altitude when he was struck by the car.

2014

We installed a perch at the nest that we hoped would lure the adults into staying within view - and boy, has that perch paid off! We were a little concerned that the perch could actually deter Harriet and Ozzie from using the nest, so we held our breaths and crossed our fingers as late March arrived.

Harriet showed up before Ozzie as usual. About a week after her arrival, I was walking between my office and the ranch office towards the ospreys' nest, when I heard Harriet chip, chip, chip. I looked up and saw Ozzie doing his mating dance in the sky. What a sight and what a privilege to witness. He would circle higher and higher in the sky, then free fall towards the nest and swoop off at the last minute. He did this several times before landing, both birds chirping the entire time.

Harriet and Ozzie three eggs that season were all laid near the Lunar eclipse, so when the three chicks hatched, a D@D member suggested naming them Lunar, Sol, and Shadow. We all toasted their hatching. Everything seemed to be going beautifully for another successful year like the last.

But is was not to be. First, eagles relentlessly attacked the nest. Then a fierce summer storm hit, raising and clouding the water of the Bitterroot River and preventing Ozzie from securing sufficient food. Shadow died. But that was not the worst. It came in mid-August; an eagle killed Ozzie while he was fishing. We recovered his body and took it to Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. They had him mounted and installed at their Montana Wild Education Center in Helena. Harriet understood. She stayed long after her normal migration date to feed her remaining two chicks until they all migrated south.

All of us viewers felt drained and disheartened as 2014 ended. As I look back on 2014, I thank God for having seen Ozzie in his last mating display. It will never leave my memory. He was a magnificent bird, an equal partner to Harriet, and truly the only osprey in the world to do his famous "wing lift" to get Harriet off the eggs so that he could site them. He was one of a kind. We all miss him still.

2015

None of the viewers knew what to expect. How difficult would it be for Harriet to find a new mate? How could he possibly be as good as Ozzie? Would she return at all?

Return she did, and right on time at the end of March. She spend almost the entire month of March fixing up the nest and waiting, just waiting, seeming so alone. John Ashley took the incredible photo that serves as the backdrop to this article in April 2015. Harriet is sitting on her nest, looking and waiting, with the brilliant sun at her back and the wind in her feathers. It perfectly captures why she truly is our wonder woman hero. Regardless of the circumstances, she pushes forward, always trusting in life itself. Never does she give up. She just waits and always conquers what comes her way.

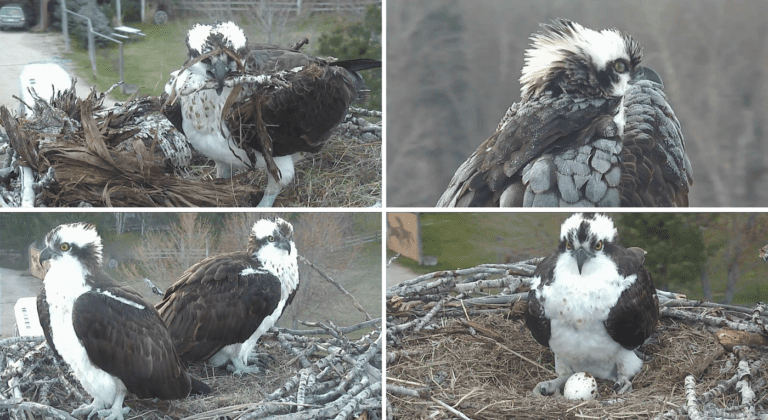

When May arrived, it seems like Harriet had placed a Craigslist ad reading "beautiful osprey widow with real estate looking for a new mate." In one wild, wild weekend no fewer than six different male ospreys came courting. In all of the frenzied activity, Harriet laid three eggs, one early on that one male pushed out, then another that was destroyed, and a third that ended up exploding at the nest form the heat. It was clear to all of us that the eggs didn't have a chance from the get go. Lacking a mate, Harriet would have to get up from incubating them, fly off to catch a fish, and leave them unattended until she returned. However, the final eggs ended up playing a significant role in the season.

After cycling through a number of mates who just didn't get the picture, Harriet finally selected a new mate that stuck with her. We named him Hal (for Hallelujah, Harriet had a mate). At times, we called him Hapless Hal, as he was obviously inexperienced and a little clumsy. He couldn't get the mating game right. He had to be nagged into getting Harriet a fish, and you could almost watch his dismay at trying to sit on the infertile egg. That egg proved its real worth in 2016. Hal did learn to sit on it' he did learn to fish for Harriet; and he finally learned all the intricacies of the mating games. However, we viewers didn't really see the results of his attending Harriet's summer school until 2016.

2016

Harriet returned to a nest that a certain someone else had taken a fancy to. Mrs. Great Horned Owl seemed very interested in the nest. Visible through via our night light and photographed my our web camera, we all worried about what would happen when Harriet returned. And, indeed, our worrying was not unjustified. A few nights after Harriet had returned, the owl was caught on camera swooping in on Harriet as she slept on the perch and completely knocking her off. Mrs. Owl could easily have killed Harriet with such a blow. To all of our relief, Harriet immediately returned to the nest and the owl was never seen again.

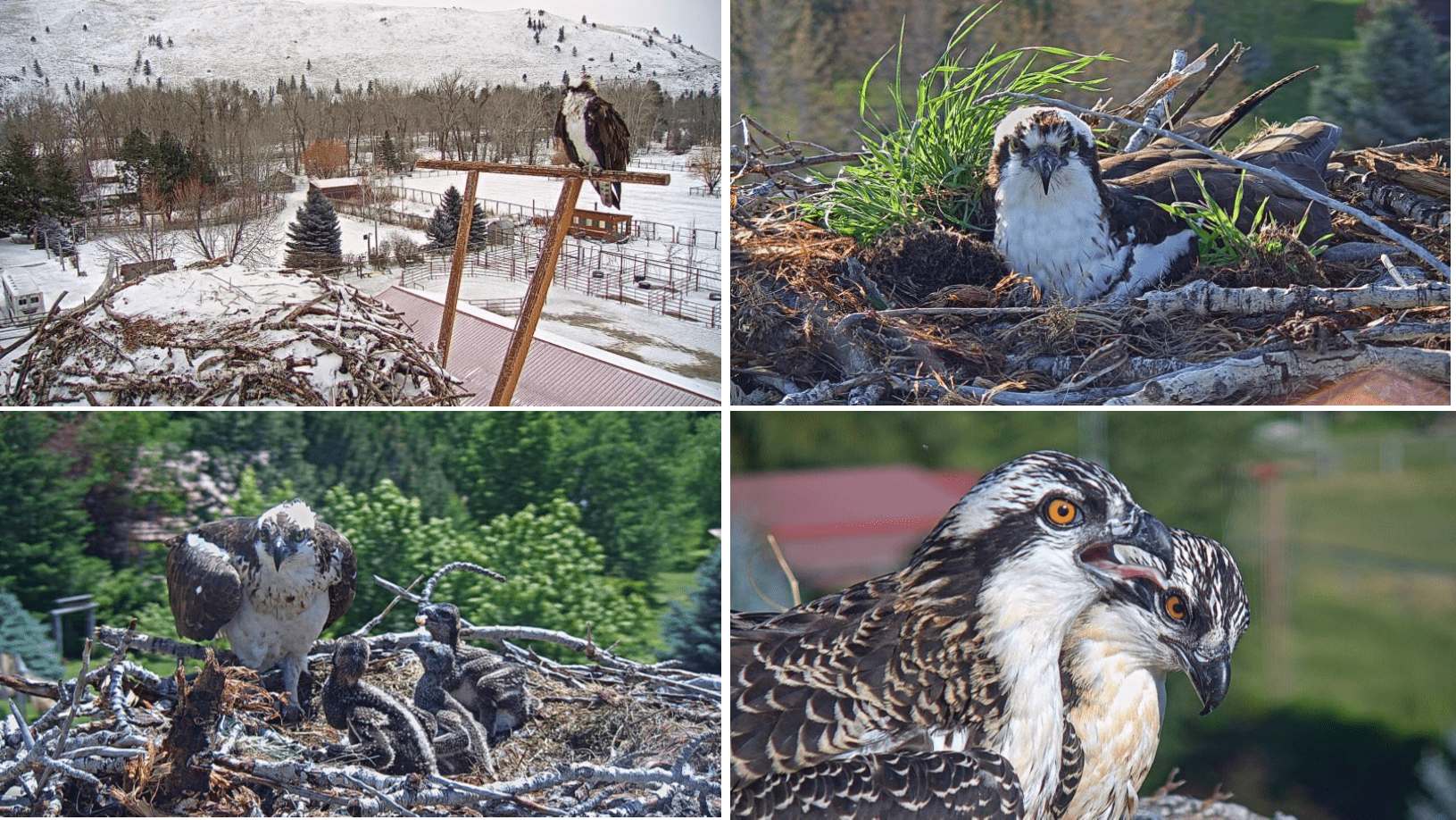

Soon after Harriet arrived, a male osprey moved in - but it wasn't Hal. Where was Hal? Well, he was not far behind and immediately displaced the interloper. Harriet and Hal then set about nest building, mating, and settling in for the season. Their two eggs were laid during the latter part of April, and the two chicks hatched on Memorial Day and shortly after, earning them the names of Honor and Glory.

It is mid-September as I write this, and Harriet, Hal, Honor, and Glory have all headed south to their winter homes. May their wings carry them far to fertile waters with plenty of fish. May Harriet, our wonder woman osprey, return to Dunrovin with Hal in tow to begin another successful breeding season.

2017

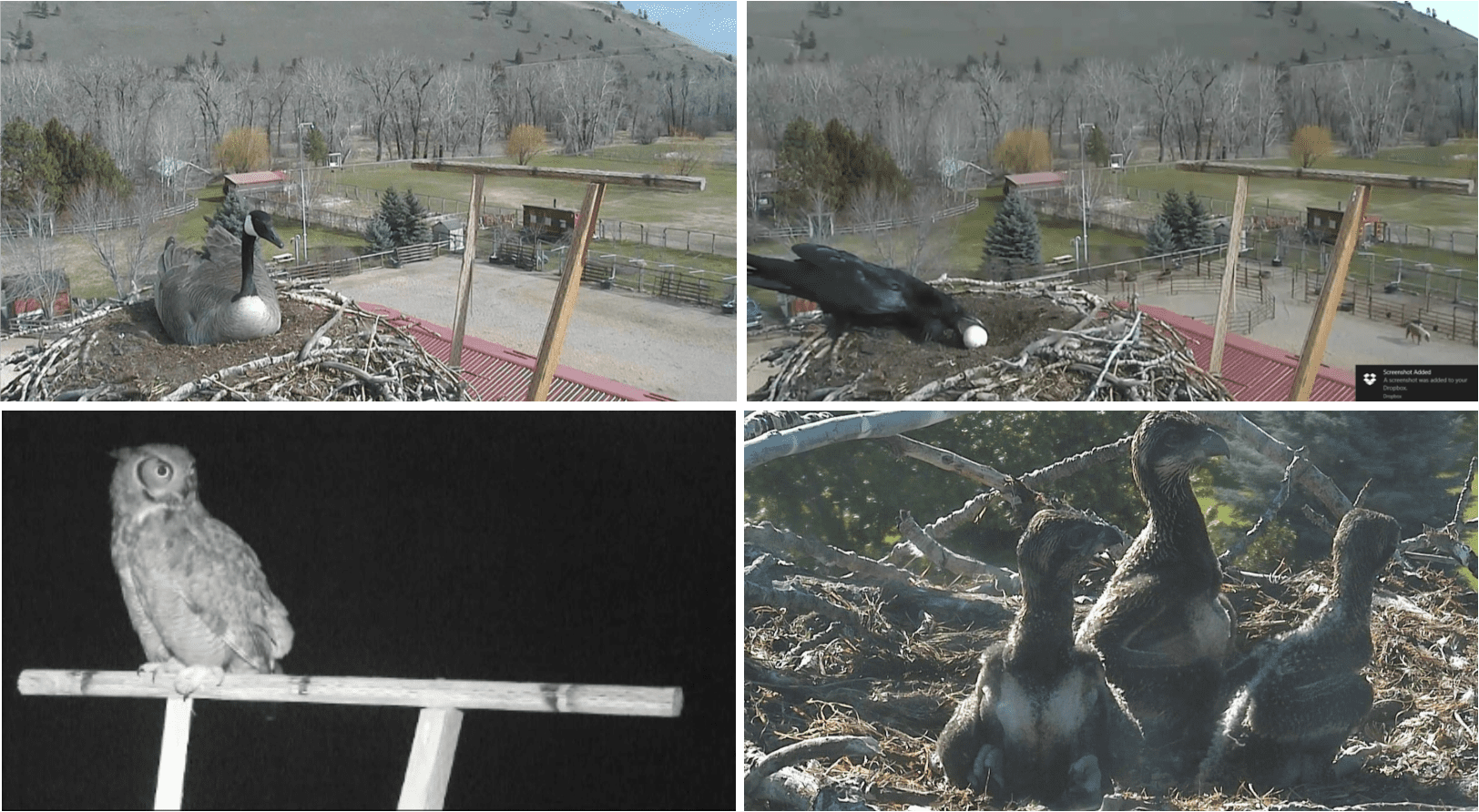

What a dramatic start! Harriet returned right on time during the first week of April. Within minutes of her landing, then taking off to catch and fish and get some much needed rest after the long migration, she returned to the nest to find a female Canada Goose who had laid an egg. While all of the Dunrovin Ranch staff on the ground fretted and made noises to discourage Mrs. Goose, it was all to no avail. However, Harriet didn't ask Mrs. Goose to politely abandon her egg, she simply dive boomed her and the goose quickly exited, leaving her egg behind.

Lacking a hand with an oppose-able thumb to pick the goose egg up and toss it out of the nest, Harriet unsuccessfully tried to roll it out. It snowed, covering both Harriet and the goose egg. It seemed that Harriet was doomed to having a goose egg in her nest for the entire summer. However, while out on a fishing trip, Mr. Raven came sneaking around the nest, checked to see if he might be caught, and quickly grabbed the egg and departed. Problem solved!

Lacking a hand with an oppose-able thumb to pick the goose egg up and toss it out of the nest, Harriet unsuccessfully tried to roll it out. It snowed, covering both Harriet and the goose egg. It seemed that Harriet was doomed to having a goose egg in her nest for the entire summer. However, while out on a fishing trip, Mr. Raven came sneaking around the nest, checked to see if he might be caught, and quickly grabbed the egg and departed. Problem solved!

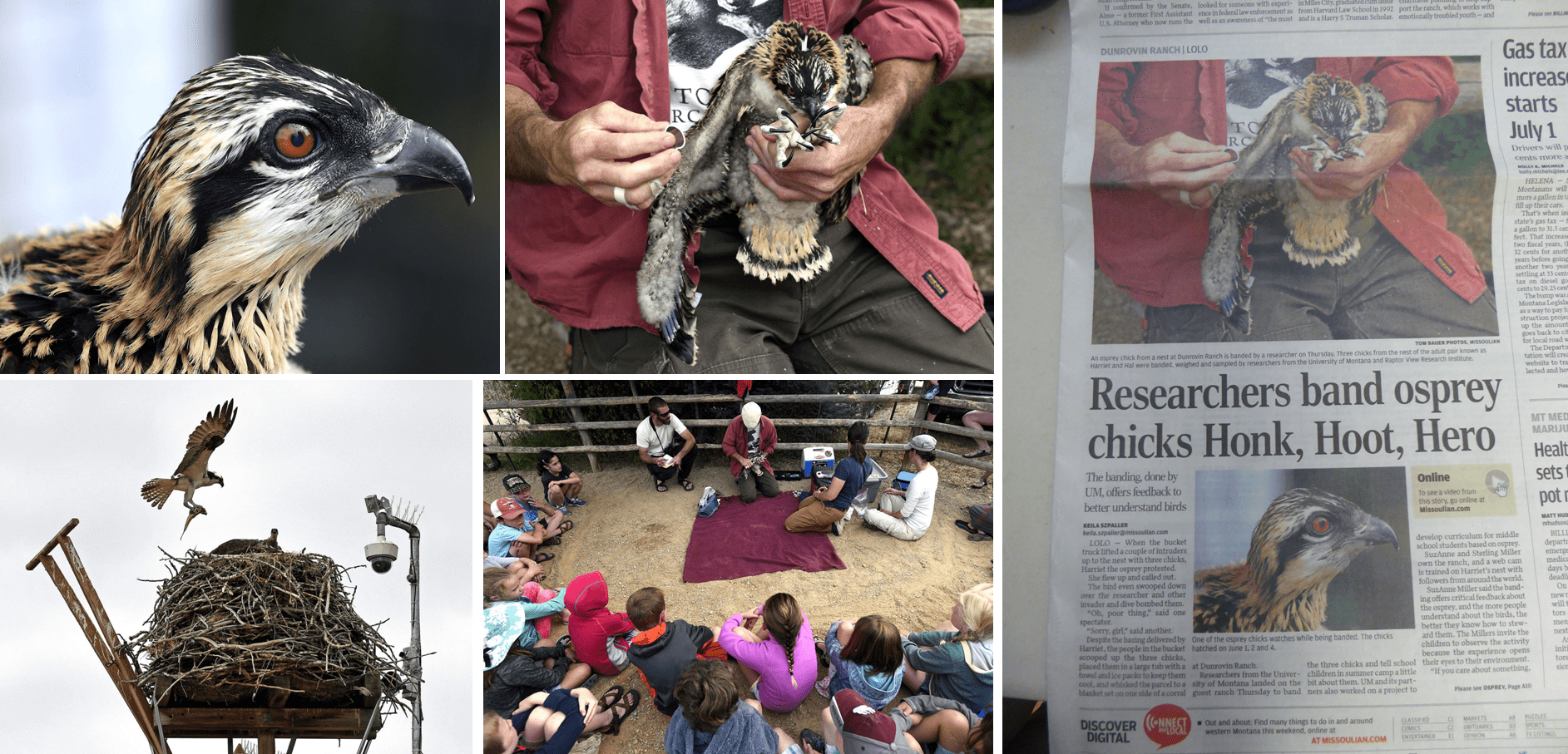

Later that night, Mrs. Great Horned Owl, knocked Harriet from her perch. Yet another big scare! Viewers were ringing their hands with all the drama that was happening within the first three days of Harriet's return - and still no Hal in sight. Finally, Hal did return and the season settled down. Harriet and Hal laid three eggs and three chicks hatched. We decided to honor the chaotic start to the year by naming the three chicks, Honk (for Mrs. Goose), Hero (for Mr. Raven), and Hoot (for Mrs. Great Horned Owl).

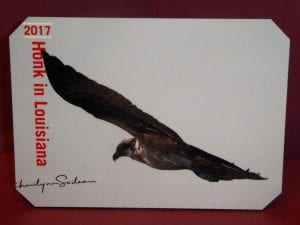

Unfortunately, summer storms caused the river to flood and food was insufficient to keep all three chicks thriving, and Hoot died in early July. The other two successfully fledged and departed in early September. The wonderful surprise was that in late November, Dunrovin Ranch received a lovely photo from bird photographer Cheri Lynn Soileau of Honk flying off the coast of Louisiana.

2018

Harriet and Hal returned right on time, got down to the business of mating, and laid three eggs. During May while they were incubating their eggs, Dunrovin sponsored a school science project called Awesome Ospreys in which students collected data to study the difference between the brooding behaviors of Harriet and Hal. The study showed that about 70% of the eggs incubation and brooding is done by Harriet. The fourth grade class from St. Joseph's Elementary School participated and were so enthusiastic about the project that they convinced their teacher to bring them all out to Dunrovin Ranch to see the nest. When the eggs hatched, we decided to let these fourth grade students name the chicks. They selected Congo, and Jambo in honor of a a new student who moved to Missoula as a refugee from the Congo. The local TV stations did a broadcast about their participation in the naming.

It was clear within a couple of weeks of hatching that the two oldest chicks began to completely dominate the youngest. At first, Hal was able to bring sufficient food so that once the two older chicks were stuffed, the youngest, Jambo, was able to get enough to thrive. However, within a few weeks, summer storms flooded the Bitterroot River, and the number of fish brought to the nest fell from over five per day to less than two. The chicks rates of growth during this critical period is such and they cannot survive long without food. To everyone's sadness, the youngest chick died.

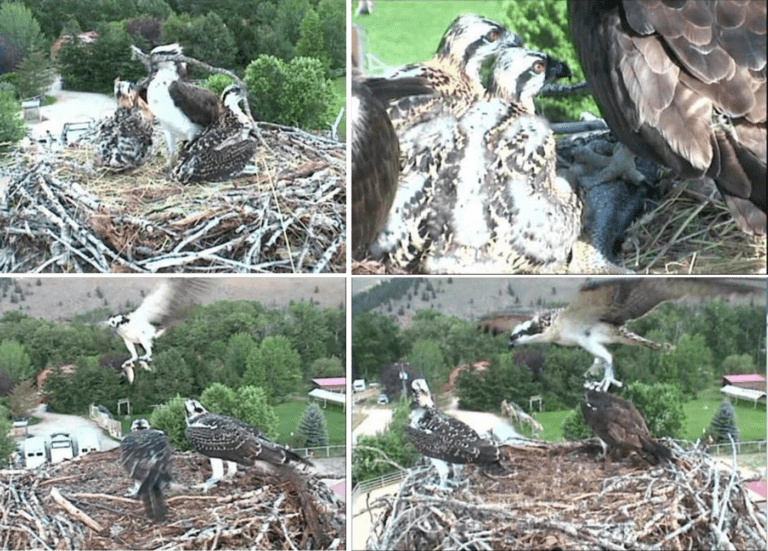

Luckily, the two older chicks not only survived, but thrived once the river's waters subsided. With dark feathers appearing on the breast and by their large size, we judged them to be two females. Perhaps we should say two FEISTY females. These two fought over nearly every fish that was brought to the nest. The tug of wars would last for minutes, and often would end with a fish going over the side of the nest. This pattern was so prevalent that the fox family that we living in the area leaned to look for food under the nest. On more than a few mornings, our webcam viewers would see several foxes lined up under the nest waiting for a fish breakfast. Take a look at this video of one such morning!

Osprey Ecology

Ospreys are one of only three birds of prey that live on all continents except Antarctica. The other two being Barn Owls and Peregrine Falcons. These resilient, magnificent birds sustain themselves with a diet almost exclusively of fish. With special adaptations to their talons, eyes, and wings, they are as masterful fishermen as they are long distant flyers.

The best possible reference for osprey ecology is Cornell University's AllAboutBirds website. Below are some highlights of these unique birds.

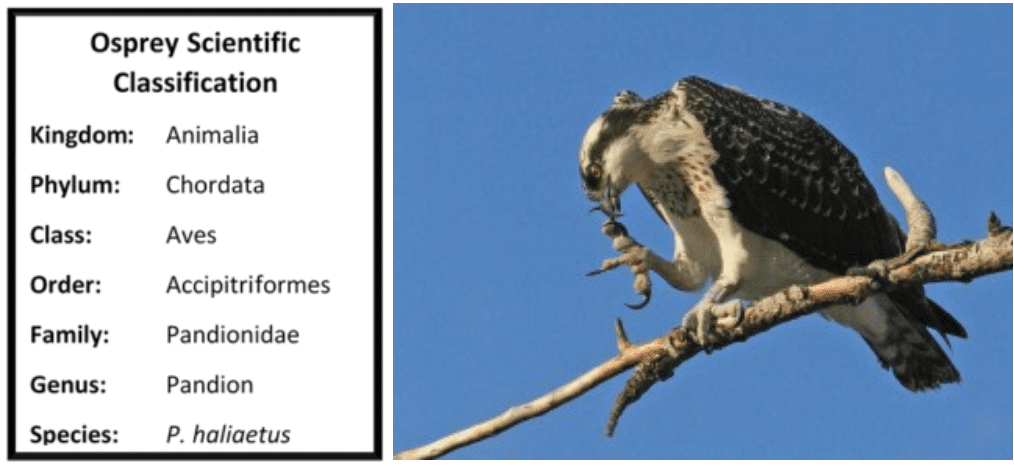

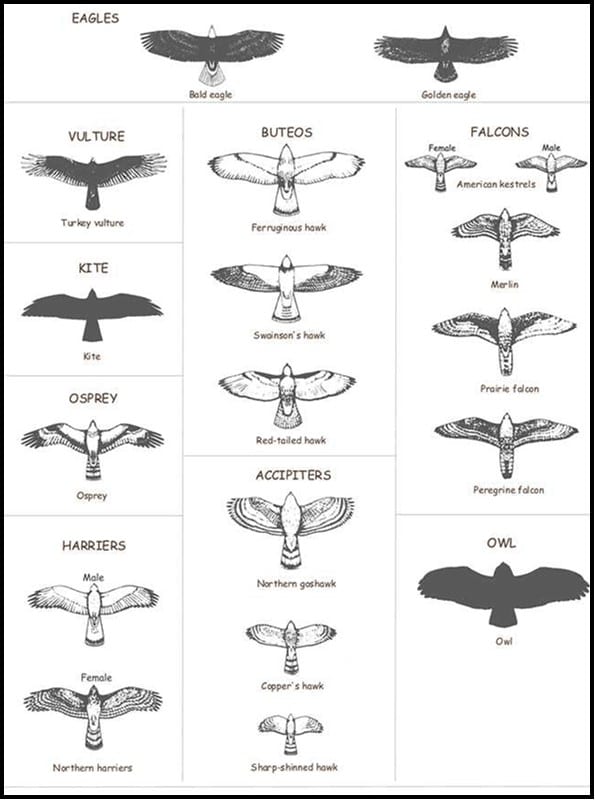

Osprey and other raptors such as hawks, eagles, and harriers belong to the order Accipitriformes. While ospreys are sometimes call sea hawks or fish hawks, hawks and ospreys belong to different families. Hawks, eagles, and harriers are part of the family Accipitridae, whereas osprey are the sole members of the family Pandionidae.

There are four recognized subspecies of osprey, differentiated by geographic region, with few differences between them: Pandion haliaetus carolinensis, P. h. haliaetus, P. h. ridgwayi, and P. h. leucocephalus.

The genus name, Pandion, comes from the mythical Greek king of the same name, who transformed into an eagle. Haliaetus is derived from the Greek word for sea eagle, although ospreys are not considered a sea eagle.

The common name, osprey, comes from the Anglo-French word ospriet and the Medieval Latin word avis prede or "bird of prey," which, in turn, derives from the Latin avis praedae. There may also be an association with the Latin word ossifragaor or "bone breaker."

Ospreys have been around for a very long time. Bones belonging to an earlier species of Pandion have been found in both California and Florida and are estimated to be 13 million years old.

Lifespan

With an average lifespan of 7 to 10 years, ospreys live a relatively long time in comparison to other bird species. One European osprey lived to be over thirty years old! In North America, the oldest known female was twenty-three and the oldest male was twenty-five. It is rare that individuals reach this age.

We're not sure how old the Dunrovin Ospreys are. The osprey nest preceded the Millers at Dunrovin Ranch and it was very difficult to identify individual ospreys until the web camera went up in 2011. Harriet was positively identified using close-up photographs from the web camera in 2011, making her at least 9 years old. This year' male, Howler, is new to the Dunrovin nest. He must be at least 3 years old to be breeding.

Size

Ospreys are considered medium to large raptors. Their body length is typically between 21-24.5 inches, with an average weight of 3 to 4.5 pounds. The average osprey wingspan measures an impressive five to six feet!

Geographically, ospreys vary in size based on whether or not they migrate north to breed. Tropical and subtropical species tend to be smaller than their northern breeding counterparts. Montana ospreys are on the larger end of the spectrum.

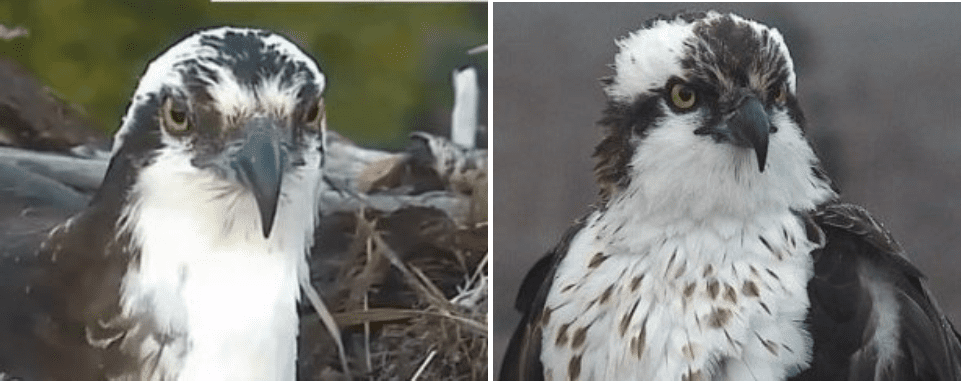

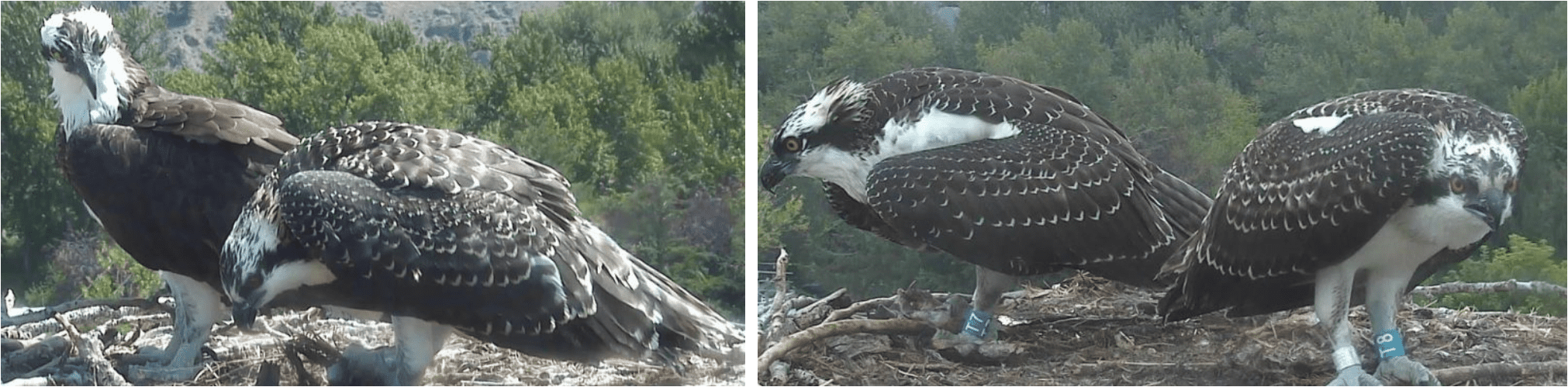

Identifying Characteristics

All ospreys have a white head with a dark stripe around each eye called the malar stripe or mask which may cut down on the sun's glare over water. Their short tails alternate dark and white bands of feathers, and they have white underbellies.Osprey wings are long, narrow, and have four finger-like flight feathers with a shorter fifth. In addition, when in flight, the silhouette of the osprey's wings form a distinct "M" shape.

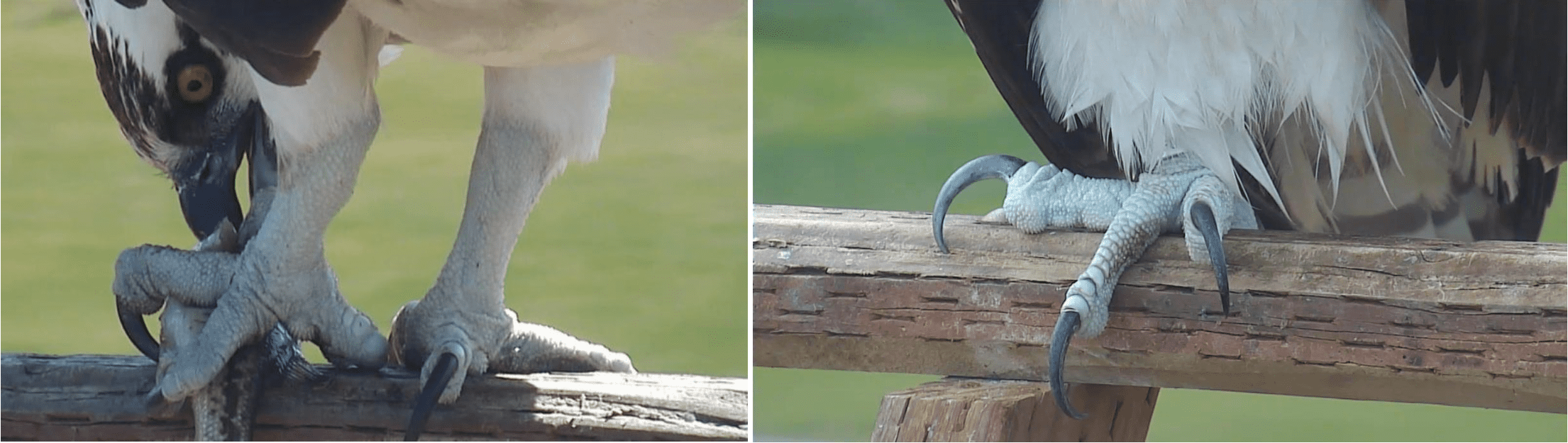

All ospreys have a black beak that coordinates well with their pale blueish white feet and black talons. Ospreys also have several distinguishing features among birds of prey. They have toes that are of equal length, and the bones in their feet are reticulated (or net-like). They have rounded talons, instead of grooved talons. The ospreys' outer toe is reversible – a trait it only shares with owls. This allows them to carry their prey with two toes in the front and two behind, pincer-like. Other features of ospreys include gripping pads or spicules on their feet, as well as reversed scales that act as barbs. With all these fancy feet-ures, one might argue that there is no better way to grasp a slippery fish!

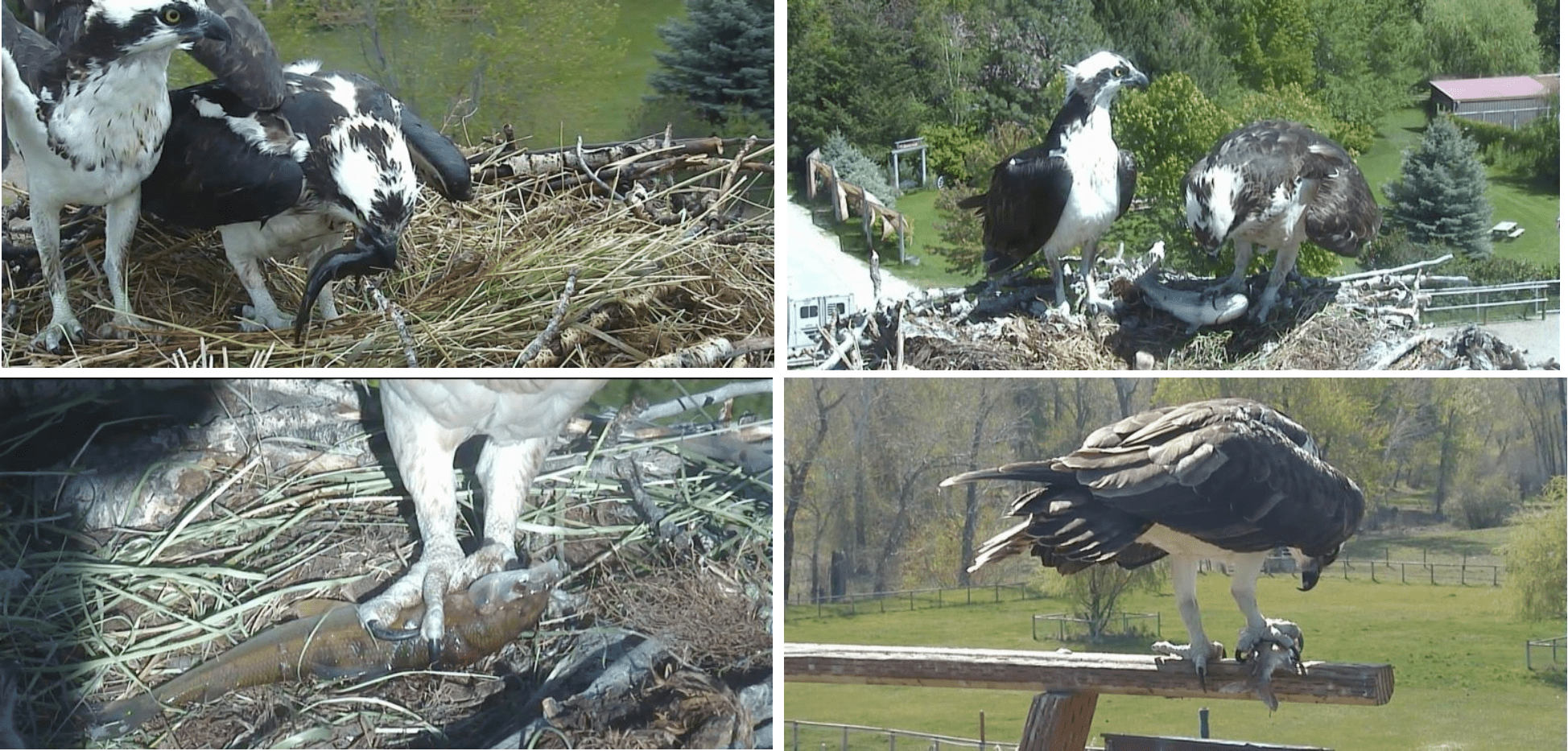

Ospreys have unique markings which are specific to individual birds. The pictures above show different markings on Hal ( the males at Dunrovin during 2015 through 2019) and Harriet. In the picture with both birds (Harriet on the left; Hal on the right) each has speckled markings on their chest. This is known as the necklace. Harriet has more speckles in her necklace than Hal. Also, Hal (center picture) has white markings on his forehead just above the beak. In contrast, Harriet (right picture) has dark markings on her forehead that touch the beak.

Raptors

People sometimes confuse ospreys with eagles, but the white underbelly of an osprey (left) is a dead giveaway. Ospreys are rightfully leery of eagles. Eagles often attack ospreys to steal the fish that ospreys catch. This is, in fact, how the first male osprey featured at the Dunrovin nest webcam died (see Remembering Ozzie Osprey). Eagles can also prey on osprey chicks as videos from an osprey nest webcam at Hog island Maine captured.

Both ospreys and eagle are raptors, also called birds of prey. All raptors have several similar behavioral and physical characteristics. They are carnivorous with strong, hooked bills for tearing flesh, powerful feet with long talons (claws) for grasping prey, and forward-facing eyes for acute long-distance vision. Most raptors molt their feathers in such a way that efficient flight is maintained at all times. They do not lose their flight feathers at the same time, but rather molt their primaries gradually, and in successive waves, starting near the body on each wing and working out toward the tip. Adjacent flight feathers are never molted at the same time.

There are many kinds of raptors, including ospreys, owls, hawks, eagles, falcons and vultures. Each kind of raptor has characteristics that distinguish it from other raptors. Ospreys are large, fish-eating hawks that plunge into the water from high above to catch fish with their talons. Osprey feet have a pivoting outer toe and sharp scales, which enable them to catch and grasp slippery fish.

Owls are silent, mostly nocturnal (nighttime) hunters. They have large eyes that gather large amounts of light, enabling them to hunt in darkness. They also have cup-like facial disks around their eyes, which help focus sound and improve hearing. Falcons have narrow, pointed wings that help them to fly fast and maneuver skillfully. They have black eyes, hooked talons and conspicuously notched bills (tomial teeth).

Vultures are scavengers (carrion eaters). They have unfeathered heads, which is an important adaptation for carrion-eating birds that poke their heads into carcasses to feed. Strong feet and sharp talons are not as important to carrion eaters because they don’t catch and transport live prey.

Accipiters are woodland-dwelling hawks. They have long, squarish tails and short, rounded wings that enable them to maneuver through trees as they hunt for small birds. These characteristics are adaptations that enable raptors to survive in their unique environments.

Raptors' Survival Advantages

- strong, hooked bill tearing flesh

- powerful talons grasping prey

- small, unfeathered head keeping clean while eating carrion

- broad, long wings soaring, searching for food

- long, narrow, pointed wings skillful maneuvering and speed

- short, rounded wings maneuvering through trees

- short flight muscles long distance flying

- notched bill (tomial tooth) shearing neck of vertebrate prey

- soft fluffy feathers muffling sound

- large eyes good vision at night

- facial disks keen hearing

Ospreys' Survival Advantages

Talons designed for catching and grasping slippery, wiggling fish

- very long and sharp

- can snap shut in 2/100 second

- base of footpads and toes covered with short, sharp spines

- flexible outer toe that can reverseposition, so there are two toes forward and two back

Legs for reaching well-down into the water

- long

- few feathers

Beaks adapted for pulling and tearing loose bites of fish

- strong and hooked

- cutting edge

Plumage needs to be waterproof and arranged to enable flight at all times

- dense and oily

- preen gland

- molt flight feathers gradually and in successive waves

Wings for strong flight for carrying fish out of the water and long migrations

- powerful muscles

- slightly bent shape

- long

.

Diet

Fish make up 99% of the osprey diet. Osprey are not particular about what fish species they eat and will generally eat what is most easily accessible. On rare occasions, Ospreys have also been known to prey on rodents, rabbits, hares, other birds, and small amphibians and reptiles.

North American Ospreys have been known to eat more than 80 different species of fish. Usually, there are two or three fish species that dominate the diet of ospreys in a specific area. Trout, cutthroat, and bull trout are native fish species of the Bitterroot River where Hal and Harriet fish. In addition, rainbow, brook, and brown trout have also been found in the Bitterroot River.

One might think that all this time around water would mean that ospreys drink the stuff, but they typically don't. It seems that their diet of fresh fish gives them enough water.

Ospreys are not known to cache fish. Leftovers are sometimes ignored and left in the nest. It is not uncommon for a ranch hand to find leftover fish in the horse corrals.

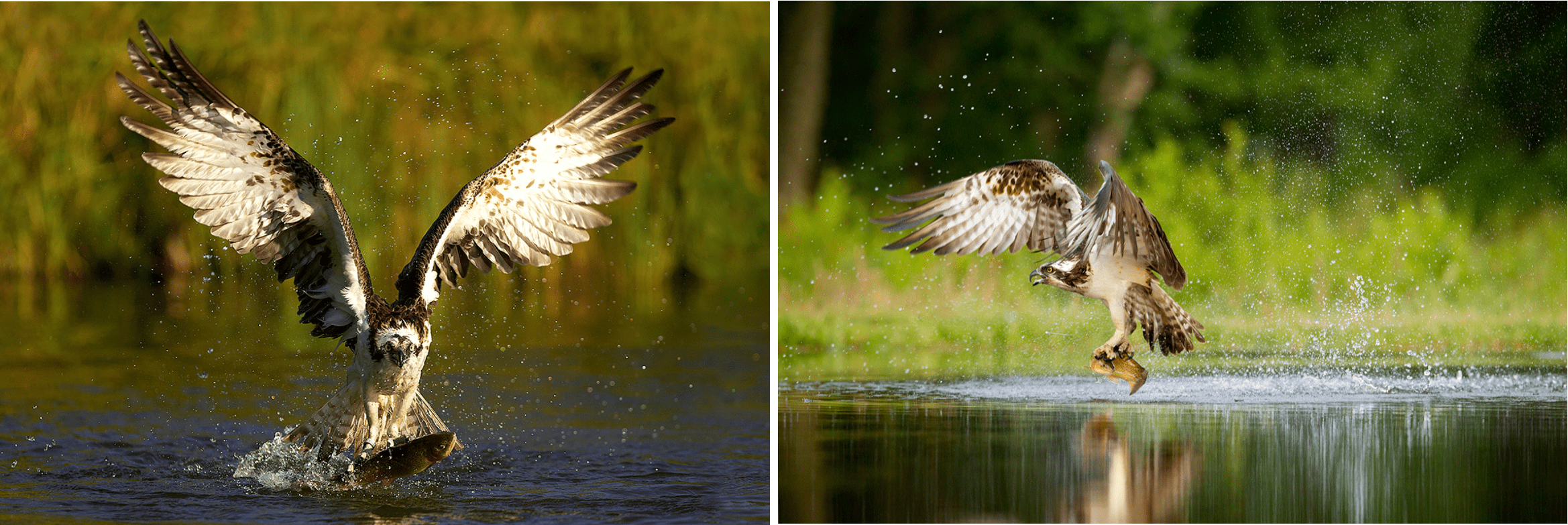

Hunting

Ospreys hunt in flight; it is rare to see them hunt from a perch. Gliding 30-100 feet above the water, they use their excellent eyesight to look for fish just under the water's surface. Once they've spotted their prey, they hover above it, then dive towards the water. At the last moment, before hitting the water, the osprey swings its legs forward and bends its wings back, so that its feet hit the water first. There is often a wild display of splashing and struggling as the bird makes contact with a fish.

Even though ospreys have nostrils that open and close and thick plumage to protect them during a dive, they can't swim. They must use their powerful wings to lift them out and away from the water with their prey in their talons. On a rare occasion, an osprey will drown after getting its talons caught in a fish that is too heavy to lift.

If you are lucky enough to see an osprey catch a fish, you will notice that its wing beats are almost horizontal when it is lifting the fish out of the water. This is when some of the greatest acrobatics occur, because once the osprey clears the water with a fish, it may re-position the fish so that the catch is headfirst to cut down on wind resistance.

Occasionally, you may witness other acrobatics. Ospreys and eagles fish in similar habitats. Sometimes an eagle will battle an osprey for its catch, forcing the osprey to drop the fish. If you are lucky enough, you may witness the eagle catch the osprey's fish in mid-air.

Hunting success depends on the skills of individual birds, weather, and water conditions (like the tide in coastal areas). Still, dives are quite successful. At the lower end, 1 in 4 dives will result in catching a fish. In ideal conditions, ospreys will catch a fish 3 out of 4 times.

Habitat

Since they rely on fish as the main source of their diet, ospreys are closely associated with water. They fish in both fresh and salt water; hence they can be found near rivers, lakes, large stream, reservoirs, coastal estuaries, salt marches, and ocean shores.

Osprey are indicators of water quality

Humans and wildlife are intricately connected to each other and to the earth, which we all share. Our ability to manipulate the environment to seemingly better suit our needs, and the close connection human actions have with wildlife populations, presents us with a great responsibility and unique challenge.

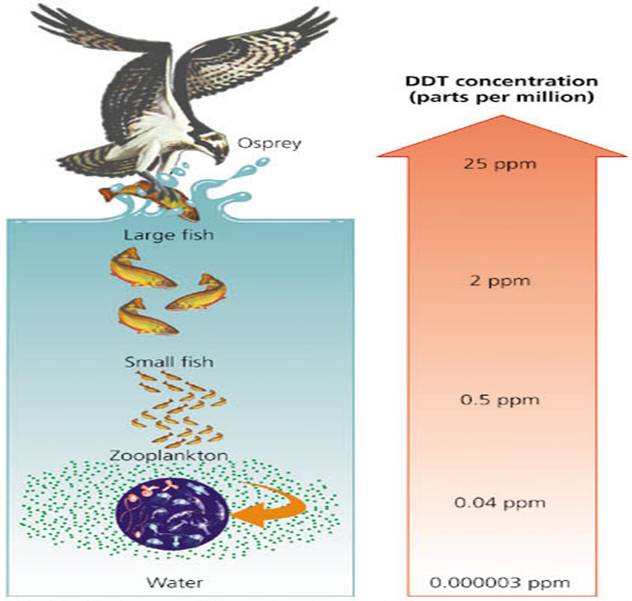

The earth’s ecosystems are so intricately woven and delicately balanced that even seemingly small changes or disruptions can have long-reaching, devastating effects. The effect of human actions on wildlife became clearly evident in the 1950s and 1960s when populations of ospreys and other raptors, including eagles, brown pelicans and peregrine falcons, in the United States dramatically plummeted to nearly unrecoverable low levels. Scientists linked the population declines to the widespread use of DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane)as a pesticide. To reduce insect damage and enhance productivity, agricultural crops across the country were sprayed with DDT. Water runoff from snowmelt, rain and irrigation carried the deadly chemical into water systems where fish and other aquatic organisms were poisoned. Also, contaminated insects and plants were eaten by fish and small birds, thus passing the poison directly to them. Those fish and birds were then eaten by raptors, which accumulated the chemical in their bodies. The accumulation of chemicals in organisms in increasingly higher concentrations at successive trophic levels, or higher steps in a food chain, is called biomagnification. Scientists found that DDT accumulates in the fatty tissues of birds, mammals and fish and that it passes through food chains. In other words, in the case of ospreys, the birds fed on large quantities of fish, which had eaten insects.

Home Ranch

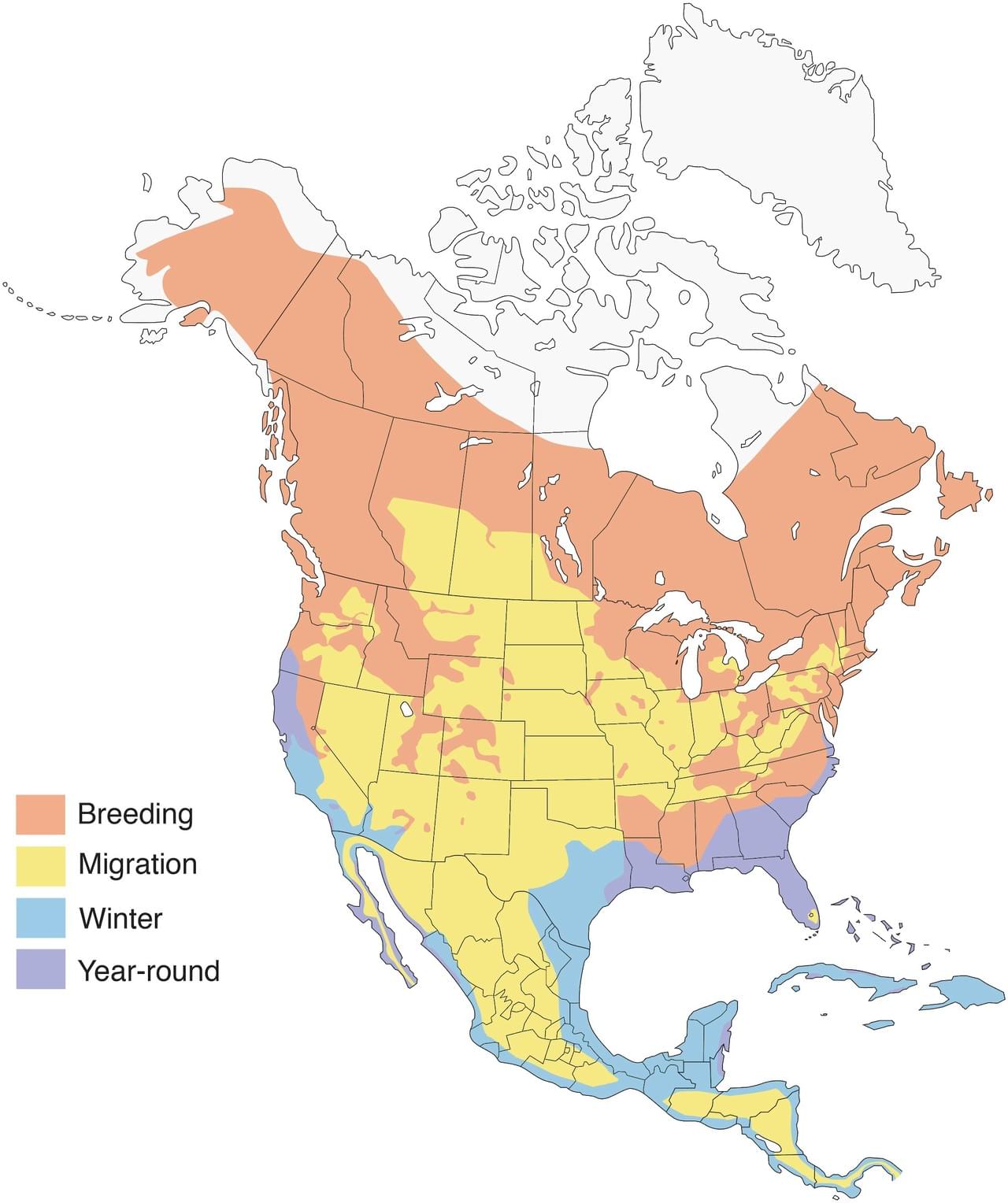

Since ospreys can live almost anywhere there is shallow unfrozen water with safe nesting sites and plenty of fish, it's no wonder that ospreys are found on every continent except Antarctica.dependence on water makes them one of the most widely distributed predatory birds. Ospreys that breed near water that freeze in winter, such as in the norther latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, migrate in the spring to their summer breeding habitats and return to southern waters during the winters. I is only during migration that ospreys are found distant from water.

In North America, ospreys are found from Alaska and Newfoundland all the way south to Florida and the Gulf Coast. Montana serves primarily as a breeding ground for the industrious birds. Below is a copy of the map from Cornell University's website AllAboutBirds.org.

Notice that Western Montana falls contains only breeding pairs of ospreys who migrate to southern areas during the winter, non-breeding season.

Migration

Most ospreys breed in one location and spend winter in another. In parts of Australia and the southern United States, however, some birds will remain at the nest site year-round. Ospreys who do not migrate save vast amounts of energy and can focus on foraging, nest building, and raising their young. Non-migratory populations breed between December and March, while migratory populations often don't return to the nest to start breeding until April or May. In addition, the early bird gets the worm, or in the case of ospreys, the non-migrating ospreys get to choose the best nesting sites near the coasts.

Scientists learn about bird migration by placing bands on the leg of birds that do not inhibit them in any way, yet allow scientists to track their movements. Occasionally, scientists also affix small radio transmitters on the back of birds to follow their daily movements.

While we'd love to have our beloved ospreys at Dunrovin all year, like most northwestern ospreys, they migrate for the winter. We're not sure where they go, because they are not banded or radio tagged, but here is some great information from Dr. Erick Greene of the Montana Osprey Project (University of Montana) regarding osprey migration in 2013:

To give you an idea of how spread out osprey migration can be, in collaboration with our research colleagues, last summer we put satellite transmitters on some ospreys at two nests about ten miles from the Hellgate nest in Missoula, Montana. The adult female spent the entire winter in one very small bay on the Nicaragua-Costa Rica border on the Pacific Ocean. The bay must be a great place to fish, since she barely flew more than several hundred yards every day all winter. At about 8 AM on 29 March she started flying north. She is headed back up towards Montana, but she is still in Mexico now. Her mate spent the winter in a mangrove swamp in Mexico on the Gulf of California. He just started north a few days ago, and he is crossing the Sonoran desert now.

Often, the female osprey will take some of her young with her on the beginning of her migration to show them the ropes. Usually, they split up along the way. The male adult osprey will stay with any lingering young until they are ready to leave the nest. In the summer of 2012, the adult male at the Hellgate nest in Missoula, Montana stayed to help one of his offspring who had a wing injury.

In North America, young ospreys follow the coastline south to Central and South America in their first fall migration. Typically, young ospreys will remain south for one-and-a-half years before returning North to establish a home territory, seek a mate, and build their first nest. Most young osprey pairs will not successfully breed until they are three years old.

Nest Location

In North America, ospreys breed along rivers, lakes, wetlands, and coastal marshes. They build their nests within several miles of the nest from which they fledged. Typically, ospreys choose tall nests in clear open spaces so they can defend the nest from land and air predators. Dead trees, buildings, rock outcrops, power poles, buoys, dock pilings, and other man-made platforms make excellent locations for osprey nests. Here at Dunrovin Ranch, Harriet's nest resides on top of a pole erected by Northwestern Energy in an attempt to keep the ospreys from building on nearby power poles.

Nest Materials

Osprey nests are large and quite conspicuous. Twigs and large sticks make up the majority of an osprey nest. Often, smaller bird species such as starlings or house sparrows live in the underside of the nest. At Dunrovin, we like to call it the basement apartment. Osprey nests can be up to five feet in diameter and two to seven feet thick. In addition, osprey nests can weigh well over 300 pounds! The weight of a 300 pound osprey nest is equivalent to approximately seven kindergartners!

Ospreys tend to return to the same nest year after year. Upon arrival, both the male and female osprey update the nest with the latest and greatest materials. The lining of the nest is typically made of softer material, like grasses or seaweed. Here at Dunrovin Ranch, Harriet and her mate often use soft horse hair and hay in the center of their nest. In addition to natural materials, ospreys have been known to use a variety of man-made materials in their nests. People have reported seeing plastic bags, flip flops, netting, sod, and bailing twine in osprey nests. Baling twine can post a serious danger to both osprey adults and nestlings.

Bailing twine is very dangerous to ospreys because their talons get easily tangled in the twine, resulting in fatality. Many ranchers and farmers use bailing twine, which makes it readily available to ospreys. At Dunrovin Ranch, we are very careful to properly dispose of all bailing twine.

Claiming the Nest

The male osprey typically arrives to the nesting territory first to claim the nest. When the male osprey arrives, he puts on a graceful aerial display, ostensibly to stake out his claim and advertise for a mate. First, he flies sharply up, gaining altitude and rapidly beating his wings. Often, he carries a fish or some nest material with him. Next, he hovers at several hundred feet with his tail fanned out. Then, he dives down, then quickly ascends again. This maneuver is repeated several times and is accompanied by singing with a loud "Creeee!" The male osprey will perform this territorial display for several days in anticipation of the female's arrival.

Harriet is an exception. She generally arrives ten to fourteen days earlier than her mate. Below is a photo taken by John Ashley of Harriet waiting in her nest while the sun sets.

Staking claim on the nest is important, because it could potentially be claimed by another species like great blue herons, eagles, hawks, geese, owls, gulls, or ravens. In 2017, a Canadian goose tried to claim the Dunrovin nest, but she didn't manage to hold it for long! Upon Harriet's return, she swooped in and immediately evicted the goose who had stolen her nest. The goose, however, had already laid an egg. Despite her best efforts, Harriet could not manage to dislodge the egg. Fortunately, a raven "stole" the goose egg and the problem was solved!

Pair Bonds

While there is evidence that ospreys mate for life, it appears that a pair returning to the nest has more to do with the nest and territory fidelity than pair bonding. However, ospreys are typically monogamous, except in the rare case when one male manages to defend two nests that are close together. In the event that one mate dies, the other osprey will typically advertise for a new one.

Male and female ospreys work together to raise chicks and cannot do it on their own. Harriet lost her first mate (Ozzie) in 2014 when he was killed by an eagle. In 2015, several male suitors came along until Harriet eventually chose Hal as her new mate. This year, Hal failed to return and Swoop fought off several other males to lay claim to Harriet and her nest.

Mating Behavior

Once the osprey reunites, a three-week period of courtship begins. The male brings food to the female. In fact, the more food the female receives, the more receptive she is to breeding. The pair will spend time together on the nest, as well. A male will protect his mate from other males and will ensure his own brood by copulating with her frequently.

Copulation is usually preceded by a mating display, from either or both the male and the female. It may occur shortly after the feeding ritual. The female will drop her wings slightly and point her tail up to one side, while the male may spread his wings and depress his tail.

If the male encounters egg in the nest that he feels cannot be the result of his mating with the female, he will readily try to toss the egg to the side. This happened this year at the Dunrovin nest. Swoop tossed the first two eggs out, he tried to toss out Harriet's third egg but she pulled in back in, and he accepted the fourth egg as his own. Hence, they are incubating two eggs this year.

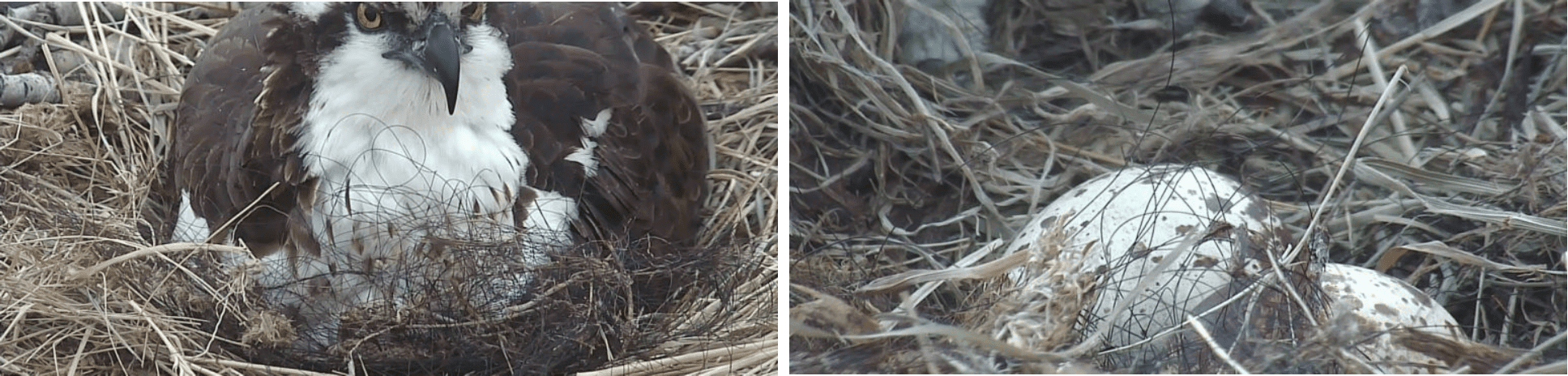

Once the first egg is laid and accepted, incubation begins. Eggs are laid from one to three days apart and a clutch usually has two to four eggs. The female osprey is primarily responsible for incubation, leaving the eggs only to feed. The male will take over until her return. After 34-40 days, the eggs hatch.

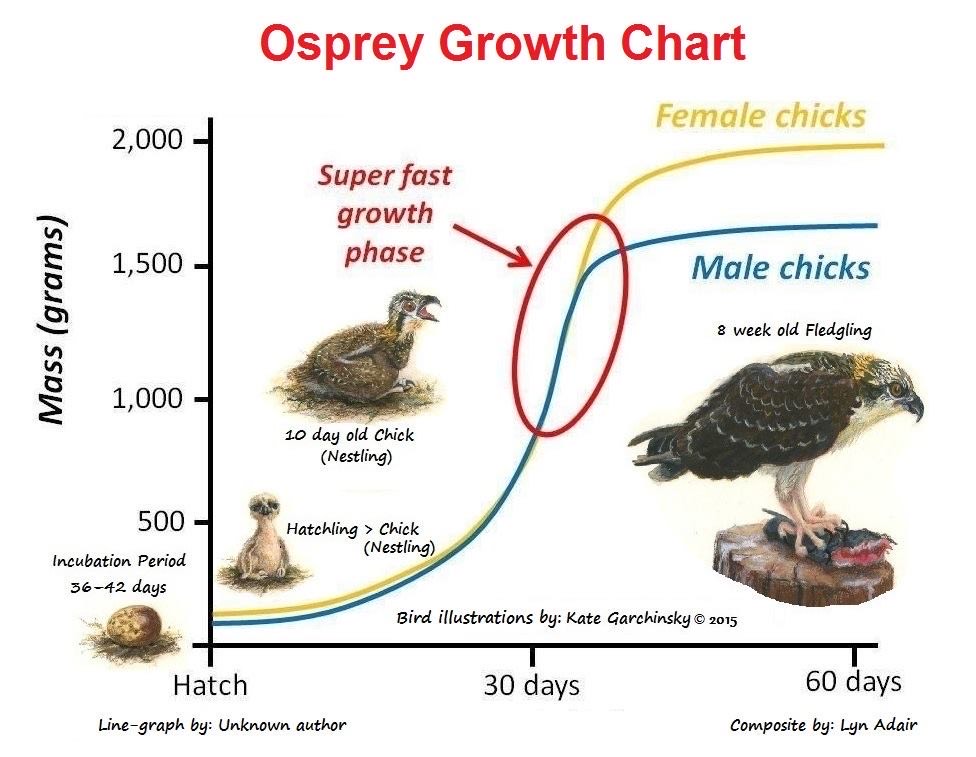

Offspring

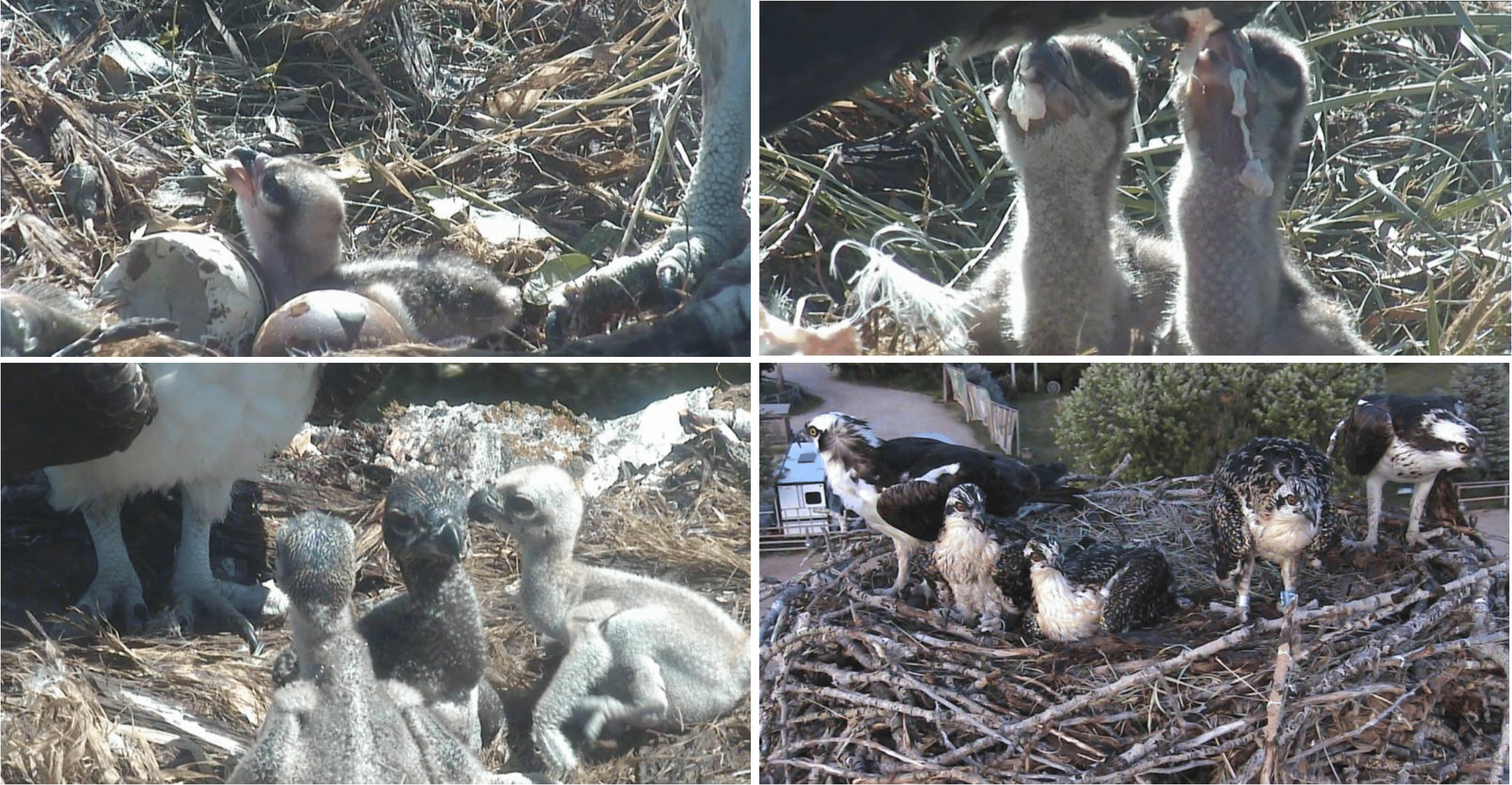

With the aid of the web cameras, you can practically watch the osprey offspring grow in front of your eyes. The offspring progress through four stages. Hatchling change to nestling within the first two weeks. Nestlings progress to fledglings through a very period a rapid growth during weeks four to six. This is one of their most vulnerable time when food demands are at the highest. Male fledgings taper off in growth before the females do.

The hatchlings are covered in fluffy white down and are small enough to be brooded by the female for the first ten days. Brooding is when a female bird spreads out her wings in an umbrella shape and covers her chicks. Through brooding, chicks make skin-to-skin contact with the adult bird to maintain body warmth.

After brooding, the female continues to protect the young by shielding them with her wings. The little brood of chicks soon sprout feathers that will slowly replace their down. Once the chicks are three or four weeks old, they start flapping their wings and are about 70-80% of their adult size. Though the nest may be up to five feet in diameter, the fledglings soon take up a lot of space and the mother will move to a nearby perch to watch over them.

The father osprey is usually the sole hunter for his family for a time. When he delivers a fish to the nest, the female tears off a piece and feeds the fledgings. Six weeks after hatching, the mother starts hunting again, delivering a fish to the nest for her growing brood, who have learned to feed themselves. At this stage, fledglings are beginning to learn to fly, but they have yet to learn to fish.

The first chick to hatch usually establishes dominance, and if the food supply is low, will often commandeer fish, at the expense of the younger siblings' survival. This is common among raptors and is called brood reduction. It ensures the survival of at least one chick in times of food scarcity.

As shown above, young chicks will flatten themselves into the nest when the adults leave the nest to chase off other birds of prey such as eagles. The chicks blend in with the nest background, helping to camouflage them from predators.

As shown above, young chicks will flatten themselves into the nest when the adults leave the nest to chase off other birds of prey such as eagles. The chicks blend in with the nest background, helping to camouflage them from predators.

Chicks' wings and back have buff-colored accents, and their necklaces are not as well defined as the adults'. Their belly also tends to be more buff than pure white, while the feathers on their head have more streaks. Their eyes also have more of an orange-red flame color, rather than the typical gold of an adult.

Juvenile ospreys resemble the adults, but are more mottled. These juvenile ospreys are almost ready to fledge.

Fledging (Time to Fly)

Young ospreys fledge - or take their first flight - at seven or eight weeks of age. Migratory ospreys, like those in the Dunrovin nest, fledge a little earlier than non-migratory ospreys. Fledglings spend time practicing and resting near the father's feeding perch, so they can still be fed by their parents. Two weeks after fledging, they begin to follow him on hunting trips. Four to eight weeks after fledging, they begin hunting on their own. They must be able to take care of themselves for their long, solo flight south. Talk about a crash course! Take a look at one chick's accidental fledge at Dunrovin in 2017.