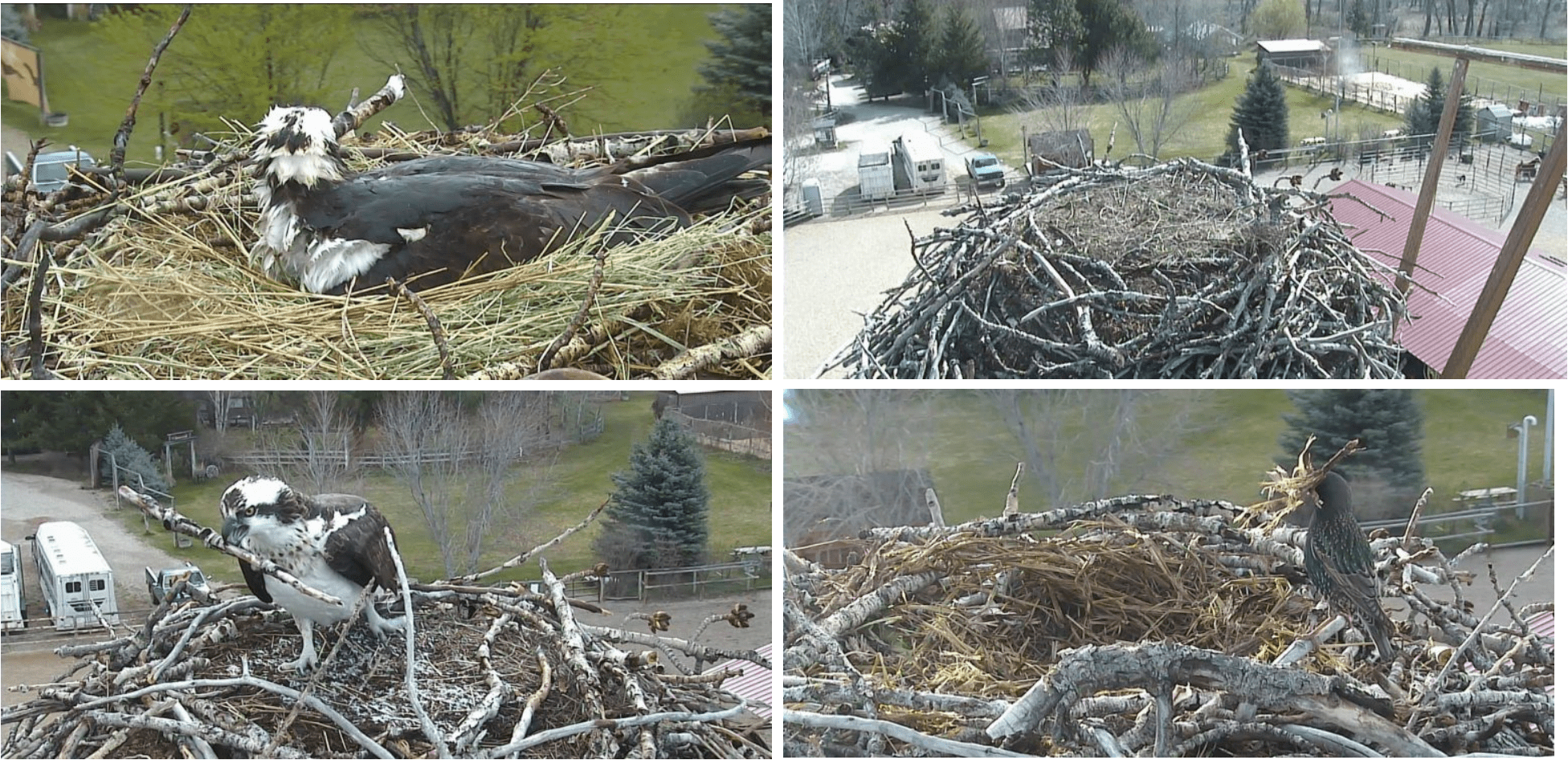

Nest Location

In North America, ospreys breed along rivers, lakes, wetlands, and coastal marshes. They build their nests within several miles of the nest from which they fledged. Typically, ospreys choose tall nests in clear open spaces so they can defend the nest from land and air predators. Dead trees, buildings, rock outcrops, power poles, buoys, dock pilings, and other man-made platforms make excellent locations for osprey nests. Here at Dunrovin Ranch, Harriet's nest resides on top of a pole erected by Northwestern Energy in an attempt to keep the ospreys from building on nearby power poles.

Nest Materials

Osprey nests are large and quite conspicuous. Twigs and large sticks make up the majority of an osprey nest. Often, smaller bird species such as starlings or house sparrows live in the underside of the nest. At Dunrovin, we like to call it the basement apartment. Osprey nests can be up to five feet in diameter and two to seven feet thick. In addition, osprey nests can weigh well over 300 pounds! The weight of a 300 pound osprey nest is equivalent to approximately seven kindergartners!

Ospreys tend to return to the same nest year after year. Upon arrival, both the male and female osprey update the nest with the latest and greatest materials. The lining of the nest is typically made of softer material, like grasses or seaweed. Here at Dunrovin Ranch, Harriet and her mate often use soft horse hair and hay in the center of their nest. In addition to natural materials, ospreys have been known to use a variety of man-made materials in their nests. People have reported seeing plastic bags, flip flops, netting, sod, and bailing twine in osprey nests. Baling twine can post a serious danger to both osprey adults and nestlings.

Bailing twine is very dangerous to ospreys because their talons get easily tangled in the twine, resulting in fatality. Many ranchers and farmers use bailing twine, which makes it readily available to ospreys. At Dunrovin Ranch, we are very careful to properly dispose of all bailing twine.

Claiming the Nest

The male osprey typically arrives to the nesting territory first to claim the nest. When the male osprey arrives, he puts on a graceful aerial display, ostensibly to stake out his claim and advertise for a mate. First, he flies sharply up, gaining altitude and rapidly beating his wings. Often, he carries a fish or some nest material with him. Next, he hovers at several hundred feet with his tail fanned out. Then, he dives down, then quickly ascends again. This maneuver is repeated several times and is accompanied by singing with a loud "Creeee!" The male osprey will perform this territorial display for several days in anticipation of the female's arrival.

Harriet is an exception. She generally arrives ten to fourteen days earlier than her mate. Below is a photo taken by John Ashley of Harriet waiting in her nest while the sun sets.

Staking claim on the nest is important, because it could potentially be claimed by another species like great blue herons, eagles, hawks, geese, owls, gulls, or ravens. In 2017, a Canadian goose tried to claim the Dunrovin nest, but she didn't manage to hold it for long! Upon Harriet's return, she swooped in and immediately evicted the goose who had stolen her nest. The goose, however, had already laid an egg. Despite her best efforts, Harriet could not manage to dislodge the egg. Fortunately, a raven "stole" the goose egg and the problem was solved!

Pair Bonds

While there is evidence that ospreys mate for life, it appears that a pair returning to the nest has more to do with the nest and territory fidelity than pair bonding. However, ospreys are typically monogamous, except in the rare case when one male manages to defend two nests that are close together. In the event that one mate dies, the other osprey will typically advertise for a new one.

Male and female ospreys work together to raise chicks and cannot do it on their own. Harriet lost her first mate (Ozzie) in 2014 when he was killed by an eagle. In 2015, several male suitors came along until Harriet eventually chose Hal as her new mate. This year, Hal failed to return and Swoop fought off several other males to lay claim to Harriet and her nest.

Mating Behavior

Once the osprey reunites, a three-week period of courtship begins. The male brings food to the female. In fact, the more food the female receives, the more receptive she is to breeding. The pair will spend time together on the nest, as well. A male will protect his mate from other males and will ensure his own brood by copulating with her frequently.

Copulation is usually preceded by a mating display, from either or both the male and the female. It may occur shortly after the feeding ritual. The female will drop her wings slightly and point her tail up to one side, while the male may spread his wings and depress his tail.

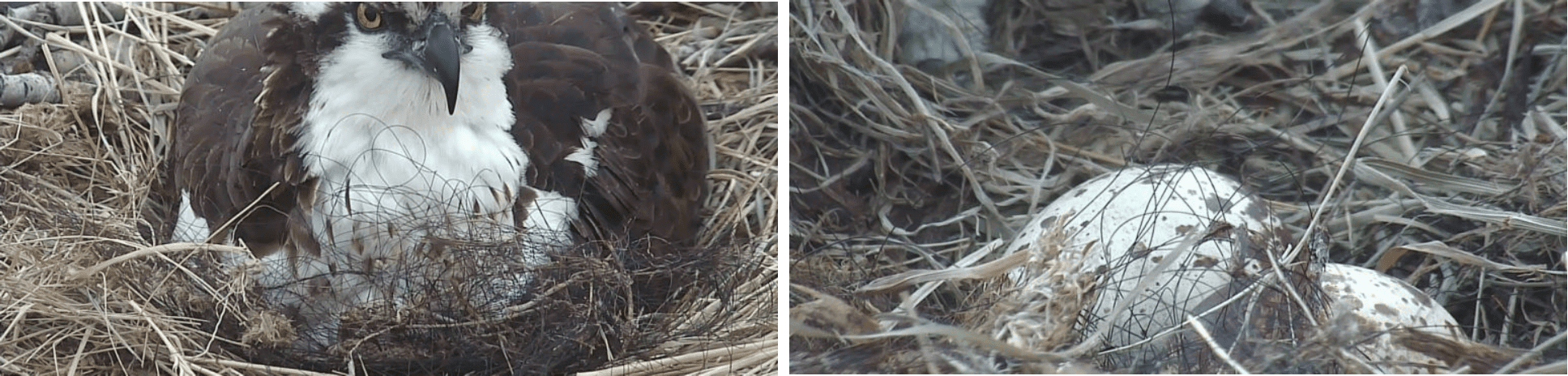

If the male encounters egg in the nest that he feels cannot be the result of his mating with the female, he will readily try to toss the egg to the side. This happened this year at the Dunrovin nest. Swoop tossed the first two eggs out, he tried to toss out Harriet's third egg but she pulled in back in, and he accepted the fourth egg as his own. Hence, they are incubating two eggs this year.

Once the first egg is laid and accepted, incubation begins. Eggs are laid from one to three days apart and a clutch usually has two to four eggs. The female osprey is primarily responsible for incubation, leaving the eggs only to feed. The male will take over until her return. After 34-40 days, the eggs hatch.

Offspring

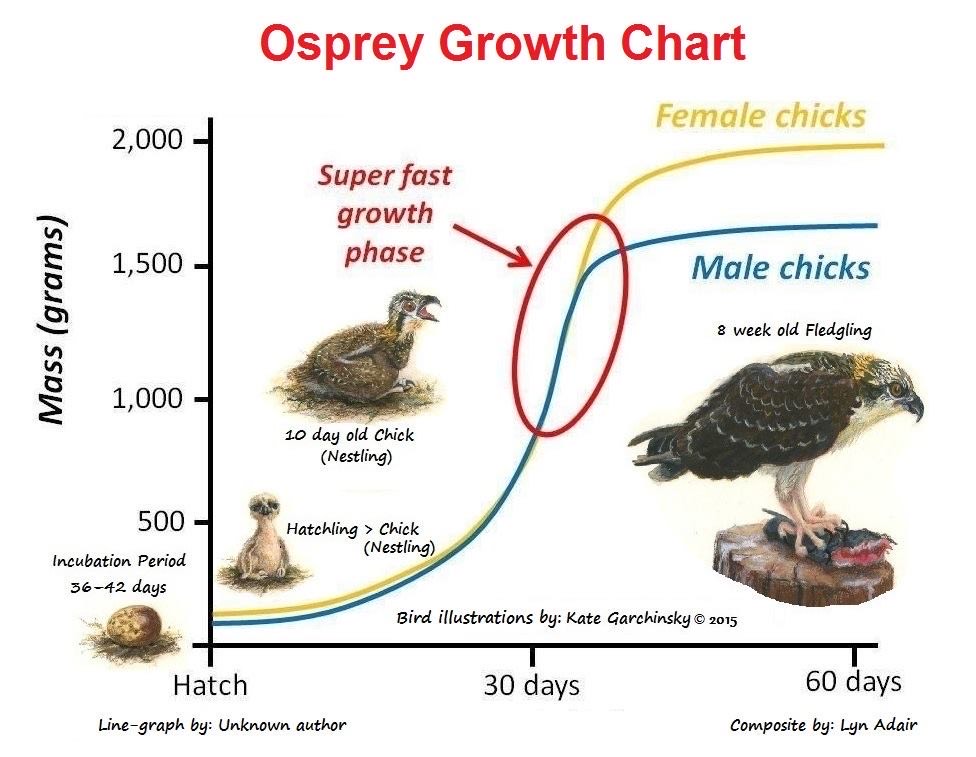

With the aid of the web cameras, you can practically watch the osprey offspring grow in front of your eyes. The offspring progress through four stages. Hatchling change to nestling within the first two weeks. Nestlings progress to fledglings through a very period a rapid growth during weeks four to six. This is one of their most vulnerable time when food demands are at the highest. Male fledgings taper off in growth before the females do.

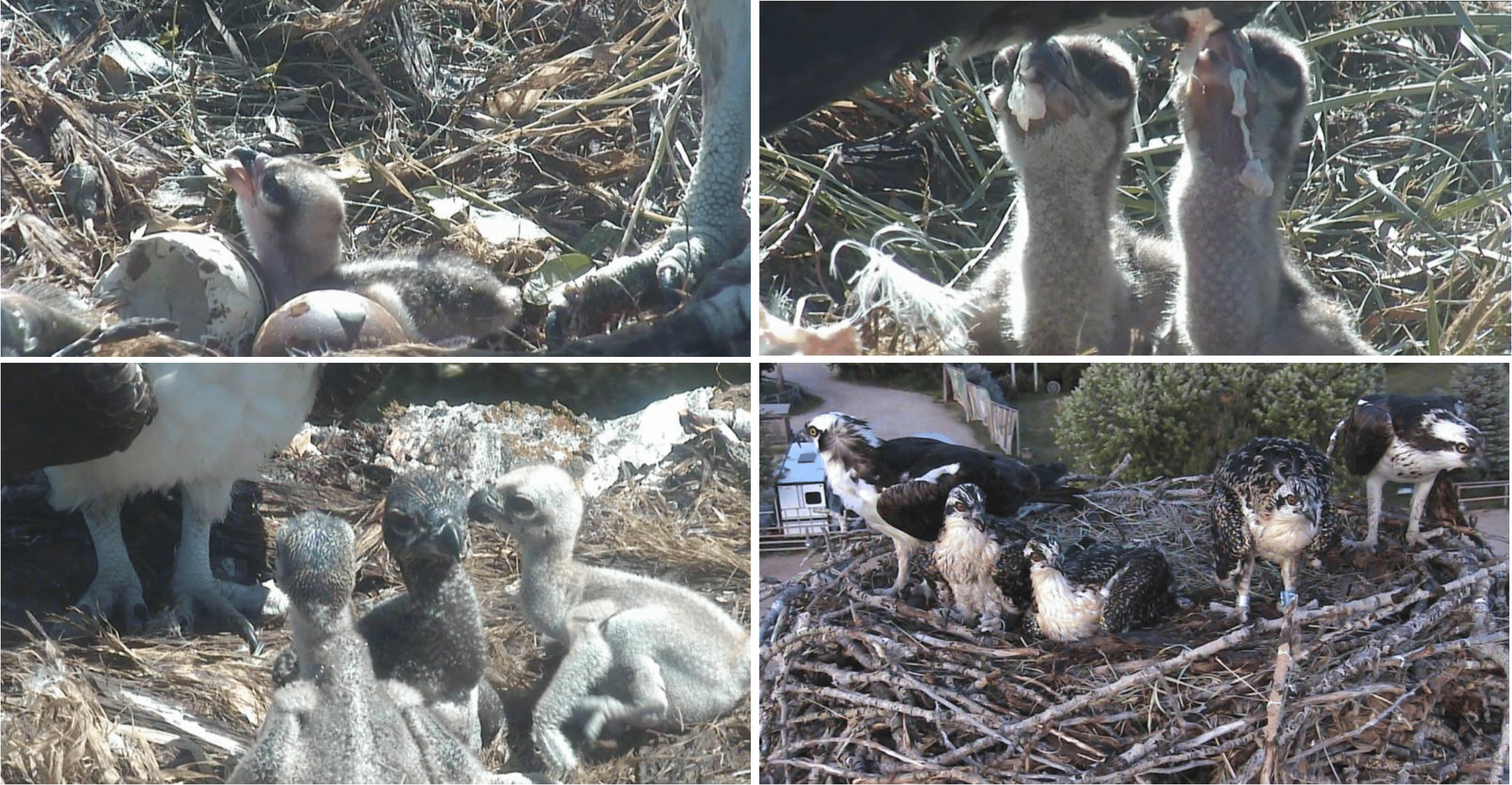

The hatchlings are covered in fluffy white down and are small enough to be brooded by the female for the first ten days. Brooding is when a female bird spreads out her wings in an umbrella shape and covers her chicks. Through brooding, chicks make skin-to-skin contact with the adult bird to maintain body warmth.

After brooding, the female continues to protect the young by shielding them with her wings. The little brood of chicks soon sprout feathers that will slowly replace their down. Once the chicks are three or four weeks old, they start flapping their wings and are about 70-80% of their adult size. Though the nest may be up to five feet in diameter, the fledglings soon take up a lot of space and the mother will move to a nearby perch to watch over them.

The father osprey is usually the sole hunter for his family for a time. When he delivers a fish to the nest, the female tears off a piece and feeds the fledgings. Six weeks after hatching, the mother starts hunting again, delivering a fish to the nest for her growing brood, who have learned to feed themselves. At this stage, fledglings are beginning to learn to fly, but they have yet to learn to fish.

The first chick to hatch usually establishes dominance, and if the food supply is low, will often commandeer fish, at the expense of the younger siblings' survival. This is common among raptors and is called brood reduction. It ensures the survival of at least one chick in times of food scarcity.

As shown above, young chicks will flatten themselves into the nest when the adults leave the nest to chase off other birds of prey such as eagles. The chicks blend in with the nest background, helping to camouflage them from predators.

As shown above, young chicks will flatten themselves into the nest when the adults leave the nest to chase off other birds of prey such as eagles. The chicks blend in with the nest background, helping to camouflage them from predators.

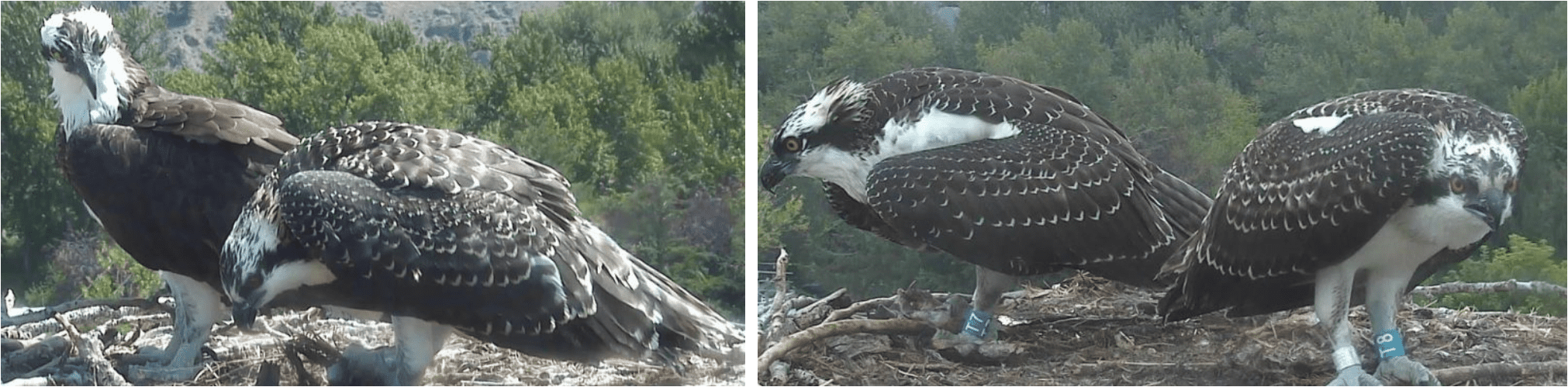

Chicks' wings and back have buff-colored accents, and their necklaces are not as well defined as the adults'. Their belly also tends to be more buff than pure white, while the feathers on their head have more streaks. Their eyes also have more of an orange-red flame color, rather than the typical gold of an adult.

Juvenile ospreys resemble the adults, but are more mottled. These juvenile ospreys are almost ready to fledge.

Fledging (Time to Fly)

Young ospreys fledge - or take their first flight - at seven or eight weeks of age. Migratory ospreys, like those in the Dunrovin nest, fledge a little earlier than non-migratory ospreys. Fledglings spend time practicing and resting near the father's feeding perch, so they can still be fed by their parents. Two weeks after fledging, they begin to follow him on hunting trips. Four to eight weeks after fledging, they begin hunting on their own. They must be able to take care of themselves for their long, solo flight south. Talk about a crash course! Take a look at one chick's accidental fledge at Dunrovin in 2017.

excellent learning material, answered a few of my questions. thank you